Cracked up about Quantum Physics

“Dr Jo joins the lunatic fringe”

I really, really shouldn’t publish this. And I’m sure there’s an easy explanation that requires absolutely no hand-waving at all. It’s just that when I’ve ventured here before, real physicists have tended to become a bit grumpy and inarticulate. Perhaps justifiably so. You’ll soon see why.

Let’s start very simply. I’ll even sketch out my plan of attack. We’ll look at the thinking behind the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics, and why it’s important (the thinking, not the prize, especially). Then we’ll take a step back and examine some basic assumptions about how space is joined up. Finally, we’ll see how the two match up. And that’s it.

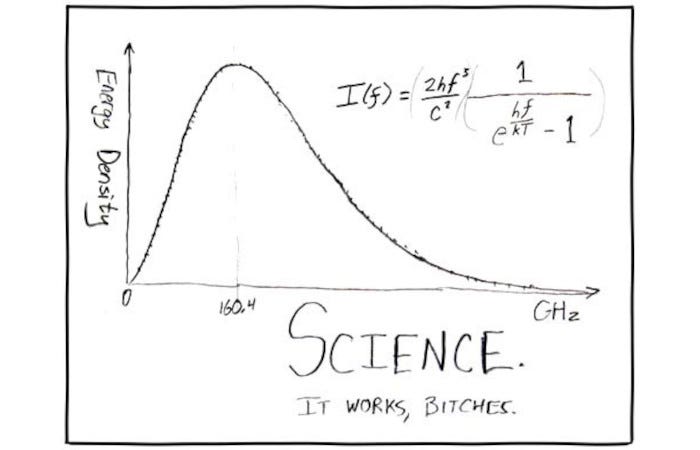

But first, let’s talk about that fabulous XKCD cartoon at the start. I’ve always loved it. The solid curve is the pattern of radiation we expect to be emitted from something very, very cool (2.73 K). That something just happens to be the entire universe, at a point about 0.4 million years after it all started, when it was cool enough to allow photons to escape.

We haven’t found a better way to explain black body radiation than Planck’s law. By far the best explanation for the cosmic background radiation is the cooling of the visible universe as it expands. And modern observations (here dotted) are so precise that if you drew in error bars for actual measurements, they would not be visible to the naked eye in a diagram of this size. Brilliant! Science works, Bitches. Specifically, the theory behind quantum mechanics works. It’s been tested repeatedly, and always comes up trumps.

This doesn’t make the theory true. In the past, I’ve gone to great pains to point out that we can never be sure about any scientific theory.⌘ You can test; you can’t validate.

EPR, Bell, and a prize

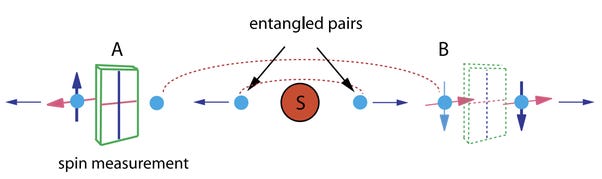

The above picture is taken from the Royal Swedish Academy’s detailed explanation why they awarded the 2022 Nobel Prize for Physics to Alain Aspect, John F Clauser, and Anton Zeilinger. Completely deserved. Brilliant work. But to start grasping it, we need to step back a fair few decades.

Nineteen thirty-five, to be precise. When (paedophile physicist) Erwin Schrödinger described ‘quantum entanglement’.1 The idea is this: it is quite possible to generate a pair of particles that are perfectly correlated. For example, if we know that a particular property (say ‘spin’) adds up to zero, then when we measure the spin of one particle (say it’s up), we know the spin of the other (it’s down).2

Just before Schrödinger coined the word entanglement (‘Verschränkung’), three chaps explained why it was all quite impossible. Or, at least, unsatisfactory. They were Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen. Yep, that Einstein. In more detail, they came up with the ‘EPR’ paradox. It works (or shouldn’t work) like this ...

Generate two entangled particles, and send one zinging off to a detector. Send another one to a second detector (B) in the above diagram. Both detectors measure the entangled property (here, spin). The theory behind quantum mechanics tells us that the process of measurement contributes to whether a given particle is spin up, or spin down. (There are no ‘hidden variables’ that pre-determine which particle is up and which is down). The bugger here is that—no matter how far removed the second particle is—it instantaneously assumes the opposite state.3

This spooky ‘action at a distance’ (‘nonlocality’) freaked out Herr Dr. Einstein and colleagues. Yet it works.4 Moving on to 1964, John Stewart Bell set out to investigate nonlocality. He came up with a variant that simply could not be explained by any hidden variable theory.5 His trick was to vary the angles of measurement and establish ‘Bell inequalities’ that depended on quantum theory.

Aspect, Clauser and Zeilinger all contributed to tests that establish at least up to the point of belief of the Nobel Prize committee (and pretty much all physicists) that hidden variables are ruled out. The logic and tests stack up. Sophisticated tests, and a deserved prize. Testing of Bell’s inequalities casts out the idea of ‘local’ properties. But what do we mean by this?

The only pun in topology

Let’s step back a bit.

Felix Hausdorff was a brilliant German mathematician who helped to found modern topology—that part of maths that deals with how geometric objects preserve certain properties when you stretch, squash, twist and bend them (‘continuously deform’ them).6 A topological space is a set of points together with how these relate to one another.

This is all relevant to modern physics, because we use topology to describe the basics of how space is joined up in pretty much7 all of our models of reality. Technically, we describe everything in terms of real numbers in a T2 topology. We commonly use the ‘double struck’ ℝ symbol to describe the reals.

This all sounds rather technical, but we should all be familiar with real numbers like -1 and √2 and π, and T2 also has a very intuitive definition: distinct points have disjoint neighbourhoods. There’s another way to explain this that introduces perhaps the only pun in the whole of topology. Another name for a T2 space is a ‘Hausdorff space’—where each point is “housed off” within its own neighbourhood <weak grin>.

It’s really important that space as we describe it is a ‘metric space’ (T2 on the three dimensional space ℝ3) as without this assumption, even the concepts of distance and angles become a bit dodgy. Calculus doesn’t work if we’re not dealing with a ‘differentiable manifold’ that is based on these assumptions. The fabulous physicist Roger Penrose is reported to have said:

“I must ... return firmly to sanity by repeating to myself three times: spacetime is a Hausdorff differentiable manifold; spacetime is a Hausdorff …

A teensy problem

Now here’s my problem. In terms of our current theories, spacetime is a Hausdorff differentiable manifold. Note the word ‘Hausdorff’ here. This assumption underpins both General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics.

But ... if one of a pair of detectors interacts with one of a pair of entangled particles, and the other particle that is far removed instantaneously assumes a correlated state, how can this space possibly be Hausdorff? As has been pointed out ad nauseam by physicists like Einstein and Bell and Aspect and Clauser and Zeilinger, this is a non-local effect.

The points in the region of the second detector at an arbitrary distance from the first surely can’t be considered ‘Hausdorff’ (or ‘housed off’) if that distant interaction can influence them.

I guess the questions here are “How can a space be both Hausdorff and non-local? What does ‘non-local’ even mean here? Can you explain the maths of this ‘non-local’ property, specifically the topology, without resorting to hand-waving?”

Now, would a real physicist step up and explain.8 Please ...

My 2c, Dr Jo.

⌘ This symbol is used to indicate posts where I’ve discussed the flagged topic in more detail.

Some readers might find it distracting (or even inappropriate) that I bring up Schrödinger’s abuse of girls. I’ve previously explained why this sort of warning flag is necessary, in discussing Otfrid Foerster.⌘

Simplistic explanations always seem to bring up left and right socks, at this point.

The ‘left and right socks’ only become left or right when you look at them. Until you measure, there’s no allocation of ‘leftness’ or ‘rightness’ (hidden variable). You cannot however use this peculiarity to send information faster than the speed of light. Despite the correlation over multiple measurements, the result of each individual measurement is randomly determined and thus cannot transmit information. The measurement is happening locally, but the outcome is random.

EPR is actually framed in terms of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, and measurement of momentum and position. Bohm thought up an example involving spin of an electron and a positron that are entangled.

Bell argued convincingly that the original EPR and Bohm’s variant could still be explained by hidden variables. His approach can’t. The interacting particle (sock, in the common analogy) does not have a pre-allocated state (sock isn’t left or right).

Tragically, on 26 January 1942, Hausdorff committed suicide together with his wife and her sister, rather than be subject to the humiliation he knew would occur in Nazi death camps.

There are a few naysayers, but they can be counted on the fingers of a mutilated hand and might be considered a bit strange (or just ignored).

I suspect the explanation will be along the lines of “ ‘Non-local’ refers to the quantum phenomenology, and has no meaning in ‘real’ space. When you have a pair of entangled particles, they simply don’t comprise (can’t be modelled as) a point or points in Hausdorff space. Only when you measure your results do they conform to the requirements of a Hausdorff differentiable manifold. The Born rule is simply an assertion that gives you the likelihood of a specific (random) outcome, without any explanatory mechanism. When you measure, the results are just there, and the local (still Hausdorff) space simply accepts them.” But I may have this completely wrong and really would like a coherent explanation. Also, it still seems like ‘spooky action at a distance’ :)

I certainly can't help with the technical part. I suspect the real problem is somehow an outgrowth of the whole "lies to children" issue.

Physicists learn how to describe the behavior of the universe by learning the MATH of it all. The math simply doesn't map very well to the concepts that monkey-brained creatures such as ourselves evolved to work with. We spent 4 billion years learning to dodge objects hurtling towards us, so classical mechanics is nice and intuitive, but once you start getting involved with the stuff that no one ever had any idea really *existed* until 150 years ago, we simply are not BUILT to get it.

I suspect the people who've devoted their lives to a field of study which ultimately cannot be described in any way which "makes intuitive sense" experience the same epistemological frustration that smart dabblers do, but they get through it because they know it WORKS. And they know with such certainty that "it works," and it was such a great deal of effort to get to that point of understanding, and when someone challenges them to reframe a set of concepts into more intuitive language, and they know they can't do it, they feel threatened.

Feynman used to say if you can't explain it to a child or a grandmother, you don't really understand it. And if he was right about that, that means no one "really" understands quantum physics. They just know how to do it, and they know it works. And that's good enough.

But it's got to be a major blow to the self-esteem, in some sense. If the people who understand physics "as well as anyone," and they STILL don't "really" understand according to Feynman's postulate, that must be extremely vexing.

I have a similar question about the wave model of light, rather like a few other members of the lunatic fringe who insist that for such a model to make any sense, there *must* be a medium involved.

Ultimately, doesn't this come down to some kind of "crisis of faith"? The laws of physics *must* be correct. Asking a pro to explain exactly why their confidence in those laws is different than religious faith in god is surely the quicker and simpler way to irritate them...

I'm not a physicist, but (you knew that "but" was coming a mile off, didn't you?) ... something that has always intrigued me is how in quantum theories the bosons operate over such different (to us) scales. You get the gluons "gluing" atomic nuclei together even though the positive charges should rip them apart. To our human senses, they are operating over unimaginably short distances and timescales. And then you get photons, which appear to be able to travel unimaginably large distances over millennia. Yet I would say that from the point of view* of the bosons themselves, they both take zero time to travel, and that therefore the distance over which they act is essentially zero. So perhaps the entangled photons are only experiencing action at a distance because to them distance is meaningless?

Perhaps our perception of the universe is wrong.

My 2p-worth. (we don't have cents where I live. I probably don't have sense, either.)

David

*(I said "I'm not a physicist", so allow me to anthropomorphise these fundamental particles and give them a point of view!)