By a narrow margin, Deming has won over ‘Orange Monday’. The result may be a little strange, though …

My paternal grandfather worked in the Post Office. It was said at the time that he married up. A bit. His wife came from an ‘educated family’ that valued the arts. And they passed this on—so my dad had a collection of ‘arty’ books, one of which contained the above image, one of Goya’s “Black Paintings”.

Which, as a child who loved exploring books of all types, freaked me out, together with Goya’s utterly brilliant The Third of May, 1808, reason enough on its own to visit Museo del Prado. The stark contrast between the mathematical precision of the soldiers and the disarray of their victims rips my heart out—as does the contrast of light and dark. And, of course, the dead people. Goya, not a huge Napoleon fan, put this so well.

But back to the image above. Goya was 70 and very deaf. He was languishing at home. Understandably, the above painting was initially kept from public display. It is said that the original even had a conspicuous boner. The oil paint was directly applied to the walls of his two-storey villa, Quinta del Sordo, and the picture later transferred to the canvas hanging in the Prado may have had some sanitising modifications made at transfer.

Traditionally, this picture is titled “Saturn Devouring his Son”, but this is not Goya’s title. In fact, he never named the picture; the victim seems to be an adult woman; and people just assumed that it fitted the enduring myth of how Cronus the leader of the Titans gobbled up his children—after he castrated his father Uranus with his mother’s ceramic sickle,1 and before he in turn was deposed by Zeus.

It turned out that like many ancient gods and modern politicians, Cronus was more rapacious than bright, and was easily deceived by Rhea into swallowing a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes, rather than the live infant Zeus. The common myth here is that Zeus and his chums then imprisoned Cronus and the other Titans in Tartarus, after separating out Atlas, who was condemned to stand forever at the Western edge of the Earth, holding up the sky on his shoulders.

The Titans would be a nice segue into 21st century Marvel fandom, but I’m not going to take the bait. I have other myths to pursue.

Myths v Legends

Surprisingly, my main topic today is indeed the work of the legendary American genius W Edwards Deming—engineer, physicist, statistician and management consultant. But let’s first clear up some points.

Traditionally we’ve decided that legends are ‘quasi-historical’: they may well be based on actual people at specific times whose deeds have become blurred and mixed up over the passage of time. In contrast, myths are made up stories that often tell moral tales involving gods, demons and whatnot.

In practice, pretty much all of our history has been tainted with mythology, and part of the process of history writing over the ages seems to be that we naturally imbue our heroes with extraordinary or even god-like qualities. Myths, legends and other stories blur together. You can even watch this sort of thing happening in real life today. Turn on Fox News and see how a felonious, incontinent and dementing sex offender is transformed into a god-like being, as just one example.

There’s also a seamless transition between myths and fairy tales, and between legends and folk tales. Perhaps the second-oldest tale of the lot is that of The Smith and the Devil, where a blacksmith makes a pact with an evil being, selling his soul for the ability to do some serious smithing—and ultimately tricks the supernatural entity into impotence.2

The Oldest Tale?

And the oldest tale of all? Very possibly the ‘Seven Sisters’. In Greek mythology they are the daughters of Atlas, who saved his sisters from that ancient hunter and undeniable rapist, Orion.3

How? In typical Greek fashion, Atlas transformed the Pleiades into stars. And we encounter very similar stories, almost wherever we look.4

Astronomers Ray & Barnaby Norris have even written a paper on the subject, where they point out that despite, well, rather limited early contact between Greeks and Australian aborigines, the latter too have a myth about a hunter (again, the star we call Orion) trying to rape the seven sisters. Another fascinating dimension is that on a dark, non-light-polluted night, most people can see just six sisters, yet pretty much every myth talks about seven of them. Every mythology also seems to have a complex reason why the seventh sister is hiding. There’s an American myth from the Onondaga that one of the siblings sang as she ascended, and became fainter; in Islam, the seventh star fell and became the Great Mosque.

Their compelling Figure 4 is shown above—where they point out that the myth may be 100,000 years old, originating in Africa. Everyone got the same myth. We pay so much attention to stories precisely because they sustained us for most of our history—and before. In many Aboriginal cultures, part of the initiation into manhood was teaching about all the visible stars in the sky, as was the case with Onodaga tribeswomen.

These ideas are not without controversy, but they do make a good story, don’t they?

Another fine story

I have another tale for you. Already, mythological elements may be accreting. It’s as follows.

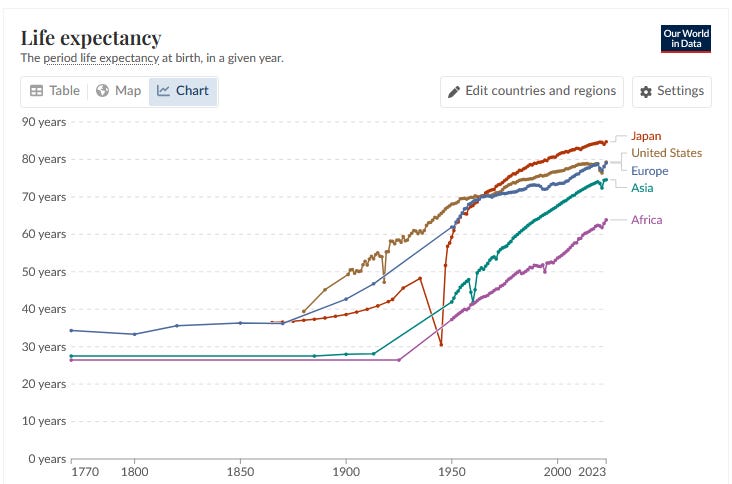

After World War II, Japan was broken. You can see this in their life expectancy graph above, obtained from Our World in Data. (Can you spot COVID-19 too?) The Japanese also had a long-term reputation for making second-rate knock-offs that they wished to shake. The fact that they did is history. Now, if you want a reliable car, buy a Toyota. If you want an unreliable POS, you can still buy [insert name of US car manufacturer here]. The tariffs won’t help much, either. But how did Japan achieve its miracle?

The LA Times has one story for us. Under MacArthur, the power of Japan’s traditional families was broken; Japanese monetary policy was tightened up; but the US did one other thing. It brought in Deming. In the LA Times version, he influenced Genichi Taguchi, who modified and disseminated Deming’s approach, and the rest is history.

In another version, Deming gave a single lecture to the assembled captains of Japanese Industry, after which they came up and asked “Mr Deming, if we do precisely what you say, how long will it take us to transform or broken economy into something that is the envy of the West?” He said “Five years”—and they did it in three. This is echoed in a YouTube video by Mike Negami.

I like the version—perhaps more close to the truth—where Deming actually spent a lot of time in Japan, talking to people. Between June and August 1950, he taught quality control to hundreds of engineers, managers and academics. He was surprised how receptive they were to Walter Shewhart’s methods, which I’ve already discussed briefly:

But Deming added something more. Several ideas that resonated with the Japanese, and still to this day don’t resonate with US manufacturers, middle managers, and politicians. Because they don’t understand. To be fair, I think they get all lost with the control charts, so the rest of Deming must surely read like alien hieroglyphics to them. You see, in Japan, JUSE (The Union of Japanese Scientists and Engineers) had already been studying Shewhart. Deming’s 14 points fell on fertile ground.

Fourteen Points, then

Deming wrote a lot—but I don’t think he was a particularly good writer. His book Out of the Crisis is actually quite a difficult read. Even his 14 points may strike you as a bit too zealous. But here they are. Try not to get stuck—run them through your common-sense filter:

Create constancy of purpose toward improvement of product and service, with the aim to become competitive and to stay in business, and to provide jobs.

Adopt the new philosophy. We are in a new economic age. [Western] Management must awaken to the challenge, must learn their responsibilities, and take on leadership for change.

Cease dependence on inspection to achieve quality. Eliminate the need for inspection on a mass basis by building quality into the product in the first place.

End the practice of awarding business on the basis of price tag. Instead, minimize total cost. Move toward a single supplier for any one item, on a long-term relationship of loyalty and trust.

Improve constantly and forever the system of production and service, to improve quality and productivity, and thus constantly decrease costs.

Institute training on the job.

Institute leadership. The aim of supervision should be to help people and machines and gadgets to do a better job. Supervision of management is in need of overhaul, as well as supervision of production workers.

Drive out fear, so that everyone may work effectively for the company.

Break down barriers between departments. People in research, design, sales, and production must work as a team, to foresee problems of production and in use that may be encountered with the product or service.

Eliminate slogans, exhortations, and targets for the work force asking for zero defects and new levels of productivity. Such exhortations only create adversarial relationships, as the bulk of the causes of low quality and low productivity belong to the system and thus lie beyond the power of the work force.

Eliminate work standards (quotas) on the factory floor. Substitute leadership. Eliminate management by objective. Eliminate management by numbers, numerical goals. Substitute leadership.

Remove barriers that rob the hourly worker of his right to pride of workmanship. The responsibility of supervisors must be changed from sheer numbers to quality. Remove barriers that rob people in management and in engineering of their right to pride of workmanship. This means, inter alia, abolishment of the annual or merit rating and of management by objective.

Institute a vigorous program of education and self-improvement.

Put everybody in the company to work to accomplish the transformation. The transformation is everybody's job.

Yes, but…

I can see readers categorising them as they proceed: “Motherhood & apple pie, points 1, 2, 5, 6, 8, 13 and 14, okay”; “A bit weird: 3, 4”, but perhaps OK with some Shewhart; and finally “What the f-ck!?? Points 7, 9, 10, 11 and 12”.

The bottom line is that Deming’s principles both make sense and do work. If you actually understand and apply them. Without special pleading. Now if at this point you start arguing that “The Japanese Are Just Special” or “The Japanese have an Exceptional Culture that Would Not Work in America”, and you have also truly embraced my previous recommendation that we question our most heartfelt beliefs, then grrl do I have something for you. It’s this two-part podcast from 2015, This American Life #561. It runs for just under an hour. I can recommend it if you have the time.

Yep. It’s been tried in America. It transformed the worst car manufacturing plant in America into something that produced vehicles of exceptionally high quality. But because American managers still did not understand what was happening, this joint venture between Toyota and General Motors ultimately failed.5

It’s not about parts

Deming’s 14 principles are all part of a seamless whole. Deming observed that managers as a class tend not to understand where poor quality comes from, and therefore blame the workers. All sorts of dysfunctional behaviour stems from this simple observation—but it also provides the solution. If you listen. He’s merely taking Shewhart to a logical, human-centred conclusion.

Over the past several decades, I myself have observed bad managerial behaviour up close, in hospitals. With the accompanying slogans and exhortations to do good. In the same hospital where there are posters exhorting you to clean your hands—“Its’ black and white!” the posters tell me—at the staff entrance there is a hand-rub dispenser that is seldom filled. Perhaps managers strut in the front, or are above hand hygiene? We are exhorted to meet the “five moments” of hand hygiene, but the dispenser that will allow us to do this is often absent from the bedside.

In a hospital that runs at 98% full, I’ve seen nurses breaking into tears in the Emergency Department, because the patient is about to breach some target. I see nurses allocated to manage a patient-controlled analgesia pump—but they haven’t been on the course to tell them how to do this, because in times of ‘emergency’ or ‘economic hardship’, the first thing that is always cut is the education.

At a national level, I see the same thing. In my neck of the woods, “leadership” seems to be confused with bossing people around. And I think this has a lot to do with failing to understand where Deming was coming from. Or why his way works.

Today

To this day, people visit Japan, and go to Toyota, and ask questions like “Can you tell us about Taiichi Ohno’s 14 Principles of the Toyota Production System?” They are told—but they leave no wiser, because they don’t understand the context. As we explored right at the start, good science is always about understanding the context. Even a good myth needs context. Who was Zeus? Did he have father problems? Why is Atlas holding up the sky? Why do managers still continually blame workers and treat them like things? For perhaps 100,000 years or more, myths have sustained us.6 But it’s now time to start thinking properly about them.

Were Goya alive today, I could see him re-drawing the picture at the start of my post, featuring Donald Trump as the eater. Or possibly Boris Johnson. Or a conflation of the two. I can imagine that thousands of years from now (if people are still around), post-humans may well have a myth about how close they were brought to extinction by someone with weird hair, who ate an entire country. And he would have done for the polar bears too—but they were heroically rescued. Children, they now live forever as stars in that new constellation, Justice. See there? It’s small and a bit blurry. Close to the Air Pump and the Chameleon. Which is the wrong hemisphere, but the Northern was too crowded, you see.

Myths are all around us. Unfortunately, many of these are persistent, traumatising myths—myths that have been handed down for ages from one manager to another: What We Really Need is a Strong Leader. Strong Leaders Just Know, so why consult? Asking Others is a Sign of Weakness. My Ignorance is as good as your specialist knowledge, and I’m The Boss. Powerful Slogans Will Get People Up Off Their Arses. We must Pit the Departments Against One Another, so that they Try Harder. Those who Fail Must Be Incompetent. And So On.

Don’t underestimate these myths though. Geriatric they may be, but like Rupert Murdoch they still hold power over the souls of people. Perhaps what we need is a New Mythology, where we translate something like Deming’s 14 Points into a rich set of myths, with their own pantheon, and a complex back story for each Myth?

Nah. Wouldn’t work. When we make myths, we reach into the darkness of the soul, and come up with things that resemble the painting at the start. Which might turn out to be me, consuming a hospital manager.

In contrast, we need light. It’s not just shining light onto things that are wrong. Some stories demand illumination, but we also need to show people how to make light and where to shine it, using the tools of reason and science that we are exploring.

We need to show a better way. In time, people may even take it on. After all, all the other options are nastier, aren’t they? Not that this has stopped us before.

Perhaps we need to simplify even more? Let’s see what we can do.

My 2c, Dr Jo.

(Image is from JUSE)

The white foam from the severed gonads gave rise to Aphrodite, the goddess of love; Uranus’ blood dropped to Earth and formed the Giants, Furies and tree nymphs; the cast aside sickle turned into the island of Corfu.

Where do you think the Rapunzel fairy tale came from? And perhaps even the legends that surround practically every musician of note. Although Robert Johnson clearly didn’t trick the devil for too long, if he did at all. Cirrhosis at age 27 doesn’t sound like a good trade, either.

Orion ultimately met his match after he pissed off Gaia. How so? By boasting that he would kill every animal on Earth, while hunting with Artemis. Gaia sent a tutelary scorpion—and that’s why both are commemorated in constellations that are never in the sky at the same time. The hunter, and his prey, Orion.

Almost wherever we look. In Māori culture, the Pleiades are called ‘Matariki’, and their first rising in late June or early July marks the coming of the new year. The name is short for Ngā mata o te ariki o Tāwhirimātea, which refers to the eyes of the god of wind and weather, which he plucked out and threw into the sky in a fit of rage after his parents the Earth and Sky were separated and he was defeated by the only opponent who would stand up against him, Tūmatauenga the god of war. So no, not a truly universal myth.

If you want the executive summary, you can read the Wikipedia page on NUMMI. It was closed in 2010, and then taken over by Tesla.

We Stole Fire from the Gods before we were even Homo sapiens. Don’t tell me that people who had fire and (surely) language didn’t have fire myths. Perhaps far older than the Seven Sisters.

We bought a 2004 Toyota Tacoma (truck) built in the NUUMI factory, that happened to be 20 miles down the road from us. That is a great truck. After some 200,000 plus miles we no longer needed a truck and sold it to a friend in 2017. It has doubled its mileage and still runs like a champ. From the beginning, nothing clattered or rattled or needed attention. And it’s that way still.

I find it amazing that others, especially Americans, can’t manage to do that.

Well that was a lovely odyssey for a Sunday morning. Lots to think about thank you.