Years ago—when I was even more naive than I am now, and before my first marriage broke up—we visited Thailand. Where we met a gentleman who sold us two tiny, very dark blue gems that he assured us were ‘Burmese sapphires’. I think they were synthetic corundum rather than glass,1 but who knows? The price was less than we would have paid to get a gemologist to examine them, which tells you everything you need to know. His spiel was engaging, and he went through all the customary “This is a genuine sapphire” tests. See, no air bubbles. Darken the room and look at the reflected torchlight. He was, of course, gaining our trust and setting us up to buy a large ‘diamond’ the next day.

For that meeting, we made sure that there were lots of people around and we had a clear escape route. We also took no money. It was an interesting study. He did his pitch, sensed our reticence and became increasingly garrulous, and ended with apoplectic fury as we declined and hastily departed. We were after memories and experiences, not implausibly priced diamonds. We later set one of the ‘sapphires’ in a ring, as a memento. Perhaps we were not that nice to bait him; in retrospect, we may have pushed our luck a bit. Being stabbed on a beach in Pattaya can ruin your day.

The only thing more fascinating than studying the spiel of the con-artist is studying his victims. Us. The undeniable persuasive skills of many grifters around the world have relatively little to do with their success. Far more potent is the indefatigable belief that I cannot be taken in—that I can spot deceit. “Other people are suckers, but not me. I can spot the tells.” This is the lifeblood of the scammer. We may spot one crude scam; repeated exposure to scam artists may vaccinate us to a certain extent (and is certainly educational); but there is an infinity of other scams out there. We are all vulnerable.

Whom can we trust? Do you have some rules of thumb—for example, “Don’t trust anyone who begins a sentence with a posh word like ‘Whom’?” Rather trust the honest handshake. The frank, no-nonsense person who speaks his mind? Yeah, right. Let’s explore trust.

In a recent post, I suggested that often, life is so complex that we do need to trust others—both to provide the right information, and to do the right thing by us. In fact, mutual trust seems to be the foundation of human success. But we are also easily deceived. It’s obvious that some scumbags are expert at profiting off our gullibility (and usually our greed, pettiness and malevolence too). By way of non-trivial example, seventy million people have just entrusted Donald Trump with the task of wrecking the United States as he imposes fascist rule. And if you can’t already see this in May 2025, you should read no further as you’ll either get very angry with me, or with yourself as you read on. Have a beer instead.

Axelrod

Before we examine some ways to spot deceit, especially in the field of science and its covert imitator and sworn enemy, pseudoscience, let’s lay some groundwork. It’s not intuitively obvious why co-operation should even be a thing—let alone why humans should have mutually profited from it so extensively. As we have. How does this even work? Don’t the deceivers mostly win, anyhow? Actually, no they don’t!

I’m generally not a huge fan of political scientists, but I must admit that the person who brought this home to me several decades ago was political scientist Robert Axelrod. Perhaps because his primary specialty is not games theory, I’ve witnessed a few game theoreticians put the boot into him, but I’ve generally found their criticism weak and unconvincing. Axelrod rose to prominence in the early 1980s, especially after Douglas Hofstadter featured his work in his Metamagical Themas in Scientific American.

The attraction of his work is not just that it is explanatory. It also works. We start with the prisoners’ dilemma—and then re-run it again and again. If you haven’t yet come across this, here’s how it goes:

Two people are arrested on suspicion of having committed a theft. There are no particularly close ties between them, and they are held in separate cells, with no possibility of communication. The prosecutor goes to each in turn and says “We have enough circumstantial evidence to pretty much guarantee that each of you will be put in the clink for two years. But If you testify against your ‘colleague’, then he’ll get five years, and you get off scot free.” Not being silly, each prisoner asks the key question “But what happens if we both rat one another out?” The prosecutor responds “Well then, I’m afraid you both get four years. Think it over”.

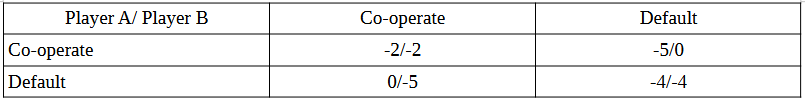

The horns of a dilemma! There’s a strong temptation to betray the other person—so both do, and both are disadvantaged. If they’d just kept quiet, they would have lost less. This also introduces the idea of a “payoff matrix”:

You can easily work out what happens here. If both prisoners “co-operate” by not ratting out the other, they get 2 years; if A betrays and B doesn’t, A gets 0 years and the sucker B gets five; but if they mutually default, then they both get 4 years of incarceration. For this to be suitably confronting, we emphasise that 0 > -2 > -4 > -5 is the number of years taken away from you in the various combinations.2

The really interesting question though is “What happens if we run this scenario repeatedly?” Is there merit in being ‘nasty’ or ‘nice’, once you have some experience of interacting with the other person? Axelrod pursued this question. He organised a computer competition, where you could submit your program (however complex or simple, however smart or banal) and it would be run repeatedly against all of the other submissions on an equal basis. He even organised a second round—after providing all participants with the outcomes of the first round.

Which were remarkable. The consistent winner in both rounds was a four-line computer program written in BASIC called “Tit-for-Tat”. Its behaviour was blindingly simple: The first time, co-operate; then mirror the response of the other program. If they co-operated, do so too; if they default, do this until they co-operate again. Tit for tat.

Despite some very smart theoretical minds contributing, Tit-for-Tat consistently won in the long term. Axelrod identifies several characteristics that seem to work:

The program is ‘nice’— it’s not the first to default.

It’s ‘forgiving’—if you change from default to co-operate, the program will also become nicer.

It’s not too nice: there is retaliation for a default.

The program is explicit in its strategy and evidently does not try to screw you. A program that is either inscrutable or clearly ‘on the make’ will elicit less co-operation.

He then goes on to assert that these properties are desirable in human interaction, and provide a logical basis for co-operation. Win-win. Of course, in reality, things become more nuanced. But at least we have a reasonable basis for believing that in the large, co-operation can be a logical choice. This may be the explanation for the success of single-celled organisms that started co-operating hundreds of millions of years ago, resulting in the proliferation of multicellular organisms we have today. And us.

Over the millennia we’ve also witnessed the enormous strength of people working together. Now we have justification. The problem we currently seem to have is the one already alluded to: how do we spot an untrustworthy player? And what do we do when we encounter one?

Common sense

It’s obvious that—as with everything else in life—there are no absolutes here. There is always some possible scenario, however remote, where your most trusted confidant can betray you utterly. But that observation carries within it the seed of a solution. The words “however remote” suggest that, to a degree, trust is quantifiable. We can also work out appropriate strategies for various scenarios.

As ET Jaynes pointed out, if you see someone in a mask climbing through the broken window of a jewellery shop with a bag full of glittery stuff over his shoulder, you can construct scenarios where a reputable jeweller on his way to a fancy-dress party was forced to break into his own shop and rescue prized items; but the obvious scenario is the likely one, by a considerable margin. But how do we determine that margin? Common sense would seem to take us part of the way, but there are other considerations.

In this post, I’m going to do something a bit strange. There’s a cringey component, you see. But I’m going to do it anyway, in the interests of both honesty and illustration. I’m going to use some of my past performance as a brief case study. But first, let’s think more generally about co-operation.

(Honesty box is from https://thespinoff.co.nz/business/28-03-2018/the-honesty-box-enters-the-21st-century )

This is difficult

If the problems I’ve just outlined are as easy as the example of the jeweller in fancy dress—or my little sapphire experience at the start—we wouldn’t be in our current trouble, where vast numbers of people are being taken to the cleaners by emails claiming that they’ve “won a prize” or that there’s been a mix-up with a package delivery. We wouldn’t be deluged in fake research, for example claims that apple cider vinegar is more effective than the new weight loss drugs. An increasing number of Americans wouldn’t be on their uppers. Trust can be tricky. How do we decide whom to trust?

Historically, we often haven’t performed that well. There is a huge variety of losing strategies. For example, if we trust nobody, then we’re not fun to be with. But worse is to come. Quite because we’re human, we’ll end up having to trust someone—and because we haven’t practised co-operation and been exposed to deceit, we’ll likely flunk out. And previously, we ignored the opportunity for win-win. Axelrod.

Alternatively, we can try to rip absolutely everyone else off—à la Trump. Which can be an apparently winning strategy, for a time. The devastation is however starting already. Will Trump and his sycophants continue to have a good time over the next year or so? I have my doubts. Let’s see.3

You also do meet people who seem infinitely trusting. Often they have a surprisingly good run. It’s likely that some settings are conducive to trust; others, less so. The “honesty box” pictured above is still encountered in New Zealand, where the producer trusts you to pay for what you take. This won’t work everywhere. A few fail even more conspicuously:

Trust the most convincing person. Rupert Murdoch’s Fox news is a potent counterexample. Often we are betrayed by people who only seem to have interests aligned to our own. That’s pretty much Trump’s sole selling point—and his greatest betrayal.

Trust family. You don’t need to be a keen student of (say) Prince Harry v The Firm or the various Kennedys and Kardashians to see that this often doesn’t work out. Can you think of other examples? Rupert Murdoch again. And so on. Blood, it would seem, is indeed more stupid than water. Thicker, in a word.

Trust the power—the strongest person who seems most likely to be able to slug it out, should this be necessary.

The strongest person or the corporation with the biggest clout often turns out to be an unwise choice in the long term, especially without good controls in place. There’s a teensy problem here too. It’s risen to the surface, of late.

Word of the year

There’s a reason why ‘enshittification’ was recently chosen as ‘word of the year’ by the national dictionary of Australia and the American Dialect Society. If you haven’t encountered it yet—well, actually you have. You may just not have recognised it. Cory Doctorow, who coined the word, describes three stages:

Things seem hunky dory. A corporation commercialises a grand new idea, and people flock to it because it improves their lives, in some way. Users then become dependent. Facebook. TikTok.

The corporation then starts selling out the users to other businesses. Because they can, they also eat the opposition. So those other businesses become trapped, just like the users.

Finally, the enshittification is complete. The corporation screws their business customers too. Everyone is having a bad time, apart perhaps from the shareholders. Until the monster rots and dies.

Or, to quote Mark Zuckerberg (as Doctorow does):

I don't know why. They "trust me" Dumb fucks.

Why does this happen? Partially due to failure of regulation; corporations become too powerful. But also due to fundamentally bad design—we’ll get back to this at the end. So one clear example of “things I shouldn’t trust” is in fact power, especially where there are no consequences for the powerful when they break trust.

There’s a theme building here. Rather than looking for “things I can trust”, might we not take the reverse approach? Progressively exclude the untrustworthy?

Provenance

We already know that all good science is based on an unbroken chain of calibration. A chain of trust. Now here’s the thing—every other belief in the trustworthiness of absolutely anything demands a similar chain! If I’m going to buy an expensive gemstone or indeed an ancient, valuable work of art, or even a religion (which can be very costly) I’m a fool if I don’t research its provenance. Some dodgy bugger on a Pattaya beach is not a solid starting point, whether he’s selling gemstones, art or salvation.

The catch is, of course, that a competent con-artist is often quite good at either convincing us that in this special circumstance, we are excessively fortunate that the chain of trust is not needed. Take the offer now—it won’t last! And we complete the deceit. Or, seeing as they’re good at forging, they will apply their talents to generating that chain of false links.

Can you see where we’re going? We’re sciencing it. We know that we can never prove that something is trustworthy and genuine—but we can test along the way, and be vigilant for flaws. And we can walk away. Here’s another such test, closely tied to provenance.

Proof of Work

Particularly when it comes to assertions about science—after all, my gig—there’s something else we can look for.

Over the past decade, I’ve put up a couple of thousand posts on a website called Quora. It’s far, far less popular than X and Facebook and TikTok and so on, but claims several 100 million users per month. I have about 30 million views, and about 14k followers. My past posts there concern areas where I know a bit—medicine, computer programming, science and philosophy.

Recently, I’ve walked away.4 The problem? It’s not just one thing. Of late, I’ve received more and more disparaging comments about my honesty and competence to even talk about topics like virology and climate change. This (and the sealioning) wear you down. But that’s not why I left.

I stuck it out. I changed my writing style, when it became apparent that Quora is now focused on (a) short posts; (b) one picture at the start; and (c) a paucity of links and references. But then I realised that they are actively promoting dissent, rants and friction in order to obtain engagement. Pretty much regardless of truthful content. The algorithm rules. Enshittification. So I left.

There’s a wonderful quote that underlines the problem with Quora—and a more general issue that walks hand in hand with enshittification. It’s attributed to journalist Hubert Mewhinney in the 1940’s:

“If Jimmy Allred says it’s raining, and W. Lee O’Daniel says it isn’t raining. Texas newspapermen quote them both, and don’t look out the window to see which is lying, and to tell the readers what the truth is at the moment.”

Nobody who is promoting accurate answers to questions has any obligation to give equal airtime to truth and deranged muttering.

How do we fix this, though? In my attempts to stick around, I diligently muted and blocked hundreds of Quora users who were overtly deranged, offensive, or both. This should not need to happen. I asked myself the question “How might this all work better?”

One idea is Proof of Work. This is the slightly cringey bit. Let’s contrast me and my critics on Quora. On the one hand, we have a decade of well-structured posts, with copious footnotes and references to the scientific literature. On the other we have the work of my critics, work that consists primarily of memes and rants.

It’s often fairly easy to evaluate past performance. Tit-for-tat manages capably with the shortest of short-term memories. But we can look back further and more diligently, and see whether someone has “done the hard yards” over several years. Or not. Absence of Work is another reason to mistrust; Proof of Work is however sadly not enough. Sometimes it’s difficult to look out of the window, and even more difficult to interpret the view.

Blotting the copybook

The name “western blot” is a play on words. It all started with Southern blots—capitalised because they’re named after the English biologist Edwin Southern, who invented a way of snipping up DNA, applying electrophoresis—where different fragments move at different rates in an electric field—and then finally blotting the bits onto a membrane, where they could be identified.

Western blots, in contrast, are used to identify proteins and especially protein variants. They similarly depend on electrophoresis, and blotting and identification. Millions upon millions of papers about vital protein biochemistry use western blots. They are a key tool. Courtesy of Photoshop, they are also prone to extreme abuse.

I just read a remarkable analysis by Sholto David of the work of a former tenured professor at Yale, Wang Min. If I look him up on Scopus, he seems to have over 100 papers, many of them in prominent journals, and most of them involving western blots. In a sense, Proof of Work. But in another not. Just because someone is the last person to leave work in the evening, doesn’t mean that he’s the hardest worker—or that he’s producing good work.

Sholto is one of my favourite deconstructors of academic bullshit, and he’s done his usual capable job of documentary dismemberment—not that Yale is listening. Read the whole exposé, if you have the time. It’s huge:

It seems that there is a strong association between papers published by Mr Min, and Western blots that have been abundantly photoshopped. Copy, flip and stretch. Remarkable here is how easily Wang “Mike” Min seems to have ingratiated himself with prominent people. Above, he’s in the smiling embrace of Peter Salovey, social psychologist and president of Yale from 2013–2024.

We have traditionally trusted scientists at prominent universities, and people who have done multiple years of medical school, and successful businessmen, and lawyers who have built up a respectable reputation, and judges and so on. Sometimes proof of work is useful; but sometimes our trust is misplaced.

So what hope is there?

Lots, actually. We can only do what we can do:

We can distrust institutions and corporations if they try to trap us, feed us algorithmic shit, and don’t error correct.

We can check provenance.

We can check Proof of Work. Carefully.

We can however embrace something more—the most important thing of all. There is a multitude of other people out there, also performing checks and balances. None of our checks is guaranteed to work. But trust is not a single act, it is a recursive network of people co-operating.

We are not alone. Provided we trust appropriately and work together. Trust validates and engenders trust. Axelrod, in practice.

Fixing things

There is however a structural problem. Let’s ask: “How do we fix things? How do we build networks of trust?”

Doctorow describes a fix for enshittification that has to be built in from the start. He has two components: transmit data in response to user requests, not algorithms; and always allow people to depart with everything—no data loss. These principles are pretty general. They are principles of architectural trust. They also apply to things like medical records, where some big players are extremely hostile to you picking up all of your data and leaving. Epic fail.

There’s a lot more we can do. If you haven’t already consumed my Deming post with its strange beginning, it provides a lot more guidance on building institutions that work. There are however even broader economic principles that we can use—and this will be the subject of my next post.

My 2c, Dr Jo.

For the pay-off matrix, conventionally we’d often say that T=0, R=-2, P=-4, S=-5 (T=temptation, R=reward for co-operation, S=sucker’s payoff, P=punishment) ; as an aside, for iteration we also require that 2R > T + S. The original 1981 article by Axelrod & Hamilton is here. We now know that in some circumstances, especially with added noise or secret co-operation between related parties, other strategies can out-perform Tit-for-Tat.

Trump is not dead yet, and we don’t know he’s going to die. I’m pretty sure that when he does, he won’t be surrounded by people who truly love him, any more than Joseph Stalin was. Perhaps there will be similarities? Who can tell?

On 13 January 1953, Pravda published an editorial titled “Evil Spies and Murderers Masked as Medical Professors”. This was heavily edited by Stalin. Many senior doctors were then arrested and tortured for weeks; some were executed. On 1 March, Stalin had a haemorrhagic stroke and ended up lying in a pool of his own piss for ages. Everyone was too scared to intervene—and which competent doctor could they call, anyway? They were all in cells. After vomiting blood several times—casting a suspicion that he had been poisoned with warfarin—he died nastily. The autopsy report has never been found. Beria, the ruthless chief of Stalin’s secret police, who had slobbered over Stalin’s hand as he lay dying, rose to the top but in the subsequent infighting was shot in the head. All rather messy, but not really unexpected. Wait for the infighting when Trump dies. This will surely be the antithesis of win-win. An interesting study.

The only new posts I now put up on Quora direct you to my Substack :)

I've been slowly making the move from Quora, too. I still answer some questions, but I'm winding that down, and ramping up essays here that aren't triggered by rage-bait pseudoquestions.

To some extent, we need to rely on people or channels that we trust.

My expertise is broad and shallow, and where it is deep, it takes a lot of work.

I know enough science that I roll my eyes at headlines that tout FTL travel with wormholes, scientists are amazed, black holes were created in the laboratory, and other wishful thinking.

Getting my information through more trustworthy channels is helpful, but right now, malicious forces in my own government and media sphere that wants to pollute information with misinformation, and destroy trustworthiness where we used to expect are making it hard for me to have confidence that I can do this in the future.

It is much easier to burn things down than to build or rebuild.

At this point, the best I can do is filter out the most distrusted stuff, and stay skeptical about everything else.