The Less Bitter Lesson

Is this my midweek madness, or simply Sutton's silliness?

I remember an interesting statistical study that the speed with which … a particular problem … could be done has increased n-fold over a period of thirty years. And the square root of n of that increase was due to increased machine speed. The other square root was increased numerical methods.

Peter Lax, programmer and Abel Prize laureate who worked on the Manhattan Project, remembering way back when, in a 2003/4 SIAM interview.

The biggest lesson that can be read from 70 years of AI research is that AI researchers consistently over-call. They also tend to have weird perspectives on science, data and reality.

The 2004 Turing award-winner, Canadian computer scientist Richard S Sutton wrote a provocative piece in 2019 called The Bitter Lesson. I’ve linked to it so you can read it. It’s not long. Here, I’m going to quote a lot of it—while I point out the bits I consider silly.

Sutton seems to believe his own rhetoric about ‘more = better’.1 I think he tends to misrepresent/ignore human smarts. The crude message I get from him is an emphasis on ‘brute force’. He has a naive take on ‘simplicity’. He really believes in computer ‘scaling laws’.

In more detail

Sutton says:

The biggest lesson that can be read from 70 years of AI research is that general methods that leverage computation are ultimately the most effective, and by a large margin. The ultimate reason for this is Moore’s law, or rather its generalization of continued exponentially falling cost per unit of computation.

As Rodney Brooks pointed out in 2019, Moore’s law had already failed when Sutton wrote his piece. Now we’re seeing modern “Let’s throw 250 gigawatts at AI” stumbling. Strong perceptions suggest GPT-5 is hardly better than GPT-4,2 despite the vast amount of money, effort and time expended on programming it. Sam Altman’s desperate plan to further his AI dreams by spending trillions has been called “tone deaf and indefensible”. We’re also just discovering ‘context rot’, too.

There are no ‘laws’ that allow brute force to compensate for the wrong approach.

Two ways

The bitter lesson is nothing of the sort, there is plenty of space for thinking hard, and there always will be.

noosphr, Hacker news on ycombinator

When not reminding us that more machine gives more grunt (D’Oh!) Sutton really seems to put the boot in to his fellow researchers ...

Seeking an improvement that makes a difference in the shorter term, researchers seek to leverage their human knowledge of the domain, but the only thing that matters in the long run is the leveraging of computation. [my emphasis]

Really?

But examples!

So, let’s look at his examples.

In computer chess, the methods that defeated the world champion, Kasparov, in 1997, were based on massive, deep search.

Actually, no. It turns out that during the crucial game, Deep Blue made a software error, and Kasparov was psyched out—he believed it was thinking deeply instead.3

Of course, computers now consistently beat humans, but this is even more nuanced. Currently, Stockfish, which has a lot of heuristics made by human hands, is usually somewhat better than Leela Chess Zero (Lc0), despite the latter’s simple, self-training approach that I’m pretty sure Sutton would favour.4 And we all know that transformer-based AIs like GPT5 are rubbish at chess, sometimes not even observing the rules.

0-1, so far.5 Sutton correctly notes the superiority of throwing grunt at voice recognition and computer vision,6 rather than relying on “human-knowledge-based methods”. But he then generalises:

This is a big lesson. As a field, we still have not thoroughly learned it, as we are continuing to make the same kind of mistakes. To see this, and to effectively resist it, we have to understand the appeal of these mistakes. We have to learn the bitter lesson that building in how we think we think does not work in the long run.

Which is trivially true—how computer scientists thought we think has often been spectacularly wrong. But does this generalise to a universal truth? Naah. It can’t. That’s not how science works.⌘

What lesson should we take away?

In full declamatory mode, Sutton now says two things:

One thing that should be learned from the bitter lesson is the great power of general purpose methods, of methods that continue to scale with increased computation even as the available computation becomes very great. The two methods that seem to scale arbitrarily in this way are search and learning.

The second general point to be learned from the bitter lesson is that the actual contents of minds are tremendously, irredeemably complex; we should stop trying to find simple ways to think about the contents of minds, such as simple ways to think about space, objects, multiple agents, or symmetries. All these are part of the arbitrary, intrinsically-complex, outside world. They are not what should be built in, as their complexity is endless; instead we should build in only the meta-methods that can find and capture this arbitrary complexity. Essential to these methods is that they can find good approximations, but the search for them should be by our methods, not by us. We want AI agents that can discover like we can, not which contain what we have discovered. Building in our discoveries only makes it harder to see how the discovering process can be done. [my emphasis]

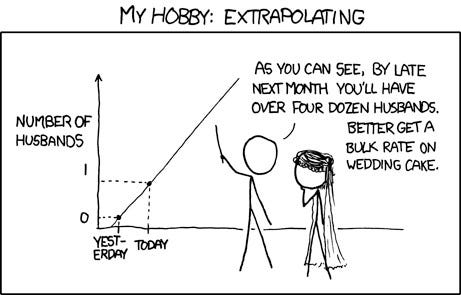

We’ve already found that ‘general purpose methods that just scale’ is shameless extrapolation. As we’ve seen with GPT5, despite chip + training costs some estimate at US$ ~5 billion, scaling just hasn’t worked. People who bet the house on LLMs are suddenly finding that Gary Marcus was right. LLMs plateau out, demanding exponentially more data.7 I guess that’s scaling, of a sort :)

Irredeemably complex?

What about (2) then? The adjective ‘irredeemably’ is a strange one for a computer scientist to use. I still think that there’s a germ of truth here—minds are (obviously) rather complex. But that’s about where the logic stops. Human minds work, and they run quite nicely on 20 watts of power.

Yes, we should “stop trying to find simple ways to think about the contents of minds” (e.g. transformers) but why should this preclude our discovering complex ways? And why should his desired ‘meta-methods’ turn out to be simple, or uniform?

There’s no reason to believe that a memory circuit in the hippocampus, visual processing in the occipital lobe, and joined up thinking in the frontal lobe will be easily implemented using a single, simple, generic approach. In fact, the ‘No Free Lunch’ theorem⌘ tells us the opposite.8

Sutton invokes ‘meta-methods’, but which ones? There’s a potential infinitude of them. He seems to be kicking the can down the road.

The Fundamental Error

When I first read Sutton’s piece, it immediately brought to mind the fundamental error I’ve talked about before⌘: the self-deception inherent in the term ‘data-driven’. Data → everything.

That’s not how Science can reasonably work, nor is ‘Computer Science’ an exception. As Karl Popper pointed out ages ago, our data acquisition depends on theory that in turn makes all sorts of assumptions. Data only turn into information when placed in context. Did Sutton succumb, and miss that data ↛ everything?

A recent, hour-long dialogue between Sutton and Dwarkesh Patel however suggests that my initial impression was wrong. Sutton spends a lot of time explaining why large language models (LLMs) are a dead end! He also reiterates the bit that I emphasised in (2) above: his plea to enable AI agents “to discover like we can.”

He makes the same points I’ve made before: that LLMs lack an inner model of the world, and that they effectively cannot be updated.9 I was quite surprised that someone who wrote something as intemperate as The Bitter Lesson could be so reasonable. Mostly. I still think that Sutton doesn’t quite get it, because he endorses the logical positivist error of ‘ground truths’—and therefore can’t answer the most important question. It’s this:

What works, then?

⥁. Closing the circle of Science: problem → model → internal testing → real-world testing (data acquisition …) → back to fixing the model, and so on. Certain uses of AI have been truly successful. Perhaps most notable of all is AlphaFold, which has been absolutely awesome at predicting how proteins fold, previously an utterly intractable computational task. This uses a combination of really smart AI tech, and human expertise, iteratively refined. We start and end by embedding everything in theory. This is surely the meta-cognition Sutton is seeking! ⥁.

We need synergy between human and machine, not monomaniac fixation on simplicity through generalisation. As Peter Lax observed in that interview at the start, we benefit from both computer power and better algorithms. Put together well.

Sutton has aged better than The Bitter Lesson. And he’s nearly 70.

⥁.

My 2c, Dr Jo.

Thanks to Google Gemini for the Nanobanana-modified image at the start. I’m all for using free tools generously donated by investors in ‘AI’.

⌘ This symbol refers to past work, where I explore the flagged idea in more detail.

He seems blissfully unaware of the ecological implications of this approach.

With surprisingly little robust, independent testing.

As revealed by Nate Silver in his book The Signal and the Noise. In addition (thanks ChatGPT for the observation) Deep Blue depended heavily on human smarts.

In addition, the searches performed by Lc0 are not particularly deep.

Sutton also mentions go-playing computers trouncing human experts. But in 2023 Kellin Pelrine repeatedly thrashed Leela Go (and similar machines) using a simple adversarial strategy. This seems to be an ongoing, broad vulnerability.

He skips over the obvious fact that you need appropriate algorithms that are, from a certain perspective, ‘simple’.

The chosen model is wrong. To hammer the last nail into the coffin lid, the ‘search and learning’ of transformers is purely associative. They just can’t do⌘ ‘generalisation’, ‘causal inference’ and ‘counterfactuals’. And they’re intrinsically, hugely energy greedy.⌘ Trillions of dollars of brute force—poof!

For example, Bloom filters⌘ are hugely efficient in determining whether a prior piece of information has been encountered before. Both software that looks up IP addresses and fruit fly brains can and do use the same principle. Is Sutton forbidding us from using such customisations? Or must we use them everywhere? Or is their use only desirable if it emerges from a more general base model?

It’s slightly disturbing seeing a bright chap like Patel completely misassess the brittle mirage of ‘chain of thought’ and be unaware of how a trained LLM can’t learn.⌘

Back in the late 1950’s, when my Uncle Bob told me about computers (I was 7 years old) I got the impression that computers could do anything, if you could instruct it properly.

I had the idea of making my own primitive computer by taking note pad, and putting answers to questions on many pages, and then you could just have some magic way of looking up the answer by just addressing it with the right question. The first small version of a Large Language Model was born.

I no longer have that notepad.

Later, I read a book that mentioned how physicists had figured out an heuristic to make their equations, that had inconvenient infinities, could be made to work if they cut off series after a certain number of terms. The called it “cut off physics”.

A thing that Turing figured out was that Godel incompleteness manifested in Turing machines as the halting problem - you can’t make a general purpose program that can look at any program and prove that it will eventually halt (complete).

I think we are trying to burn up all the fossil fuels to see whether AI will become generally and usefully intelligent if we will just burn enough fuel, and spend enough of our economic output towards that end.

Humans have a wonderful limitation, which is an actual secret to our intellectual abilities: we get frustrated when we can’t solve a particular obstacle in a particular way. We eventually stop, or die, or chose to do something different when a particular approach has used up too much of our time or resources.

I am confident that we will eventually switch off the power to these approaches that are not going to be the miracle we require. The bubble will burst, until the next one.

Wow, the part about Sutton misrepresenting human smarts really resonated. Your analysis of his naive take on simplicty and overemphasis on brute force is spot on. It’s so important to remember the human element in AI progress. A truly insightful piece.