Herbs? Gotta be good, Right?

An explosion of quackery: Part II

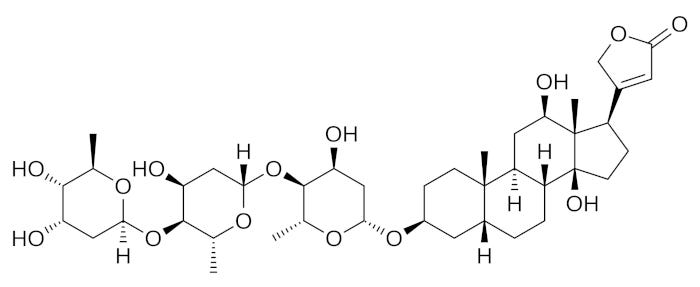

Herbs. Much of modern medicine started with herbs. But take the ‘herb’ pictured above. It has quite a story attached to it. It also has no place in modern medicine, apart from acting as a caution.

Badness in Belgium

In 1993, Belgian doctors were puzzled. Over 100 young women who attended a ‘slimming clinic’ developed kidney trouble. In many, this rapidly progressed to end-stage kidney failure, requiring dialysis and transplantation of a donor kidney. But their troubles weren’t over yet. Most of them then went on to develop cancer of the lining of the urinary tract. Similar cases were reported from other countries, too.

Why? It turns out that, as part of their wellness/slimming, these well women took herbs. Those who gave them the herbs ordered them all the way from China. They thought they were giving Stephania tetrandra but they were wrong. Here are the Chinese names of the two herbs that were mixed up:

漢防己 and 廣防己

The one on the left is indeed Stephania—Han fang ji. The root is one of the “fifty fundamental herbs” of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Rather unfortunately, the right-hand herb is our unfriend from the start: Aristolochia fangchi, aka “Guang fang ji”. It turns out that until about 2000, the latter was also used quite commonly in herbal medicines, especially in Taiwan. The Belgian disaster focused a lot of attention on it. We’ll look at it in some detail below, but first, a time-warp back to the 18th century.

Withering

In my most recent post⌘ in passing I mentioned William Withering. Let’s give him some more time, as there’s a reasonable argument that he kicked off modern pharmacology. As a botanist, physician and meticulous observer, he had the credentials. He also wrote things down carefully.

Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles, had Withering appointed to the post of physician at Birmingham General Hospital in 1775, and ten years later he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. In the same year, he published a monograph called An Account of the Foxglove and some of its Medical Uses.1 The foxglove image at the start of this section is from his book. He notes:

It would have been an eaſy taſk to have given seleƈt caſes, whoſe ſucceſsful treatment would have ſpoken ſtrongly in favour of the medicine, and perhaps been flattering to my own reputation. But Truth and Science would condemn the procedure. I have therefore mentioned every caſe in which I have preſcribed the Foxglove, proper or improper, ſucceſsful or otehrwiſe. Such a conduƈt will lay me open to the cenſure of thoſe who are diſpoſed to cenſure, but it will meet the approbation of others, who are the beſt qualified to be judges.2

I have to applaud his honesty. Would that modern practitioners of ‘herbal medicine’ and indeed real medicine all adhered to this old advice.

Digitalis, then

The main active ingredient in Digitalis purpurea, as used by Withering, is actually digitoxin, not digoxin. Despite being eliminated by the liver, the former is even more tricky to use than digoxin, as it has a longer half-life. Digoxin (derived from the related Digitalis lanata and pictured above), is therefore what we now use. Fabulously, Le Chiffre’s henchwoman Valenka used it to poison James Bond in the movie Casino Royale.

Many (but not all) plant-derived drugs are alkaloids—they contain at least one nitrogen atom. You can see that digitalis is one of those plant-derived drugs that is not an alkaloid. It’s what we call a cardiac glycoside—a steroid molecule attached to a sugar, which inhibits an important cellular ion pump in the heart.3 You can imagine that ingesting a substantial amount of such a drug will poison you quite effectively, causing death from fatal disturbances to the heart rhythm.4 Smaller doses can be safe and even useful.

Digoxin is something I still use (very occaſionally) to slow the heart rate in people with atrial fibrillation, especially if their heart is knackered. But we have the luxury of being able to check blood levels for impending toxicity; we also understand pharmacokinetic-based dosing, adjusting for sick kidneys, and the importance of making sure the serum potassium isn’t low. Withering, in contrast, flew by the seat of his pants.

The traditional story is that Withering noticed that the local witch had more success in treating patients with heart failure, and bribed her to learn the multiple herbal ingredients. It turns out that most of this legend⌘ is an embellishment of the truth by the drug company Parke-Davis as part of their campaign to market digitalis. They even gave the witch a name: ‘Mother Hutton’. But all we actually get from Withering (page 2) is:

In the year 1775, my opinion was aſked concerning a family receipt for the cure of the dropſy. I was told that it had long been kept a ſecret by and old woman in Shropſhire, who had ſometimes made cures after the more regular praƈtitioners had failed. I was informed alſo, that the effeƈts produced were violent vomiting and purging; for the diuretic effeƈts ſeemed to have been overlooked. This medicine was compoſed of twenty or more different herbs; but it was not very difficult for one converſant in theſe ſubjeƈts, to perceive, that the aƈtive herb could be no other than the Foxglove.

Withering then goes on to describe 156 cases he managed in the community, and several others besides, together with a fairly voluminous correspondence, extending to 178 pages. He systematically describes several preparations (from various parts of the plant), together with cautions about usage and toxicity. He even describes animal toxicity studies (turkeys). He tries to list possible indications.

We’ve moved on a bit

When I recently looked at⌘ the silliness surrounding age-prolonging pills and potions, I remarked on trust. Specifically, how someone might trust a person they met in a pub to give them a safe high, but not necessarily trust a drug manufactured under Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP)! Let’s look at this a bit.

What is GMP? The main theme here is quality—something we know a little about, after we saw how Walter Shewhart revolutionised quality control, and then how Deming worked out the human ‘rules’ for getting this right. There’s a lot more to GMP, though. It emphasises understanding all of the requirements: people, products, processes, procedures and premises (including calibration of equipment). This is now pretty standard.

That doesn’t mean we can abandon the exploration of herbs as sources of drugs. Our current tragedy is that we are likely losing pharmacologically useful drugs we’ve never even met, as the plants that contain them disappear during the anthropocene mass extinction.

And we already have so many herbs that proved useful. Not just digoxin, but artemisinin, atropine, capsaicin, codeine and morphine, caffeine, cocaine, colchicine, ephedrine, etoposide, irinotecan, paclitaxel, physostigmine, pilocarpine, quinine, quinidine, reserpine, salicylic acid, scopolamine, taxol, theophylline, tubocurarine, and vincristine—to name just a few.

But if you look through a modern pharmacopoeia, the new drugs we’ve developed will overwhelm the above list. We often take an existing substance and then modify it extensively to get rid of some of its nastier properties. Medicine has no time at all for toxic drugs like tubocurarine, when we have synthetic drugs that are simply superior. We’ve taken the best of herbal (and other) medicines, and largely made them better still. We’ve done this through the methodology of science,⌘ where we start with problems, make explanatory models and test them, filtering out the nonsense and the really dangerous substances. Now let’s look at one of those dangerous substances.

Aristolochic acid

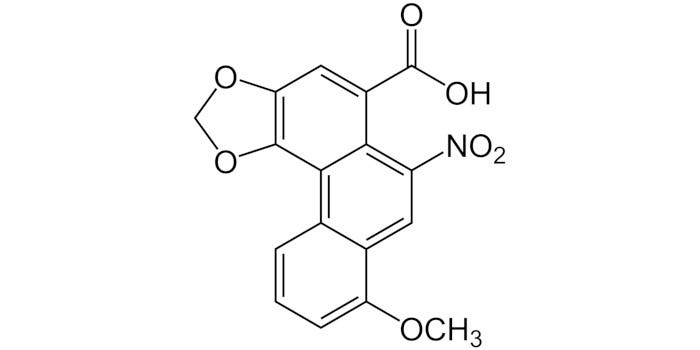

Remember those young, well Belgian women driven to renal failure and tumours? Most ended up with preventative removal of both native kidneys and ureters, which were then examined. Cancers and pre-cancerous lesions were rife, especially in those who had consumed more than 200 grams of A. fangchi. The main alkaloid precursor that did the damage is called aristolochic acid (AA). It’s nasty.

Using modern chemistry, we can describe AA and what it does rather well. We’re even beginning to understand the pathways used by Aristolochia and Asarum (“wild ginger”) to build these complex “nitrophenanthrene carboxylic acids”. Once eaten, AA is absorbed and metabolised.

An important metabolite involves joining up the -OH and -NO2 groups in the above picture.5 The resulting cyclic nitrenium ion then binds DNA. It just sticks. For years. This causes a very specific DNA mutation, an “A:T→T:A transversion”. This in turn damages key regulatory genes (e.g. p53), causing both destructive kidney fibrosis and cancer. Animal studies also show these findings.

We can even go back and look at the DNA of people with bladder cancer, and spot the transversion. Doing this, we find that AA is a global problem that explains several mysteries. Taiwan has one of the highest rates of bladder cancer in the world. The culprit here is traditional medicines that were often chock-a-block full of Aristolochia.

We also now understand the mysterious “Balkan endemic nephropathy” that caused chronic kidney failure in communities along the Danube River and its tributaries. Tissues show the characteristic transversion. It seems that some wheat fields are contaminated by Aristolochia clematitis.

“But mistakes occur with modern medicines too”

Of course they do. And it’s relevant to point out that you could take, say, aristolochic acid, and subject it to GMP, and you’d still end up with a disaster. The point though is this: you must still get the basics right. It is only reasonable to deploy the drug appropriately after you’ve ‘Scienced’ it.⌘

When we’ve dispensed with herbal healing, and move on to proper pharmacology, we will indeed discover that wily pharmaceutical companies often encourage us doctors to deploy drugs unthinkingly, with horrid effects. Those errors and deceptions don’t somehow justify the errors and deceptions of people punting herbs that haven’t been properly tested, often made using methods that are light years away from GMP.

It gets even worse. Aristolochia was investigated in the 1980s in Germany for possible anti-inflammatory properties, but discarded because it was found to be carcinogenic and mutagenic. As far back as 1964, it was identified as toxic to kidneys. Naturally, traditional herbal practitioners continued to provide it, until about 2000. They just didn’t know.

Most countries have now banned AA-containing ‘medication’. This doesn’t mean that none is being dished out, of course. Knowing that products like Guan Xin Su He, Long Dan Xie Gan Wan, and Zhiyuan Xinqinkeli contain aristolochic acid, it’s a little scary to find a recent PubMed entry that refers to one of these, and see others still being shipped internationally. And watch out for Pinyin names like guan mu tong, qing mu xiang, ma dou ling, zhu sha lian, xun gu feng, wei ling xian, xi xin and of course ‘fangji’ too (Respectively 關木通, 青木香, 馬兜玲, 朱砂莲, 尋骨風, 威灵仙, 细辛 and 防己—confusing, isn’t it?)

I strongly suspect that if hauled into the 21st century and exposed to the methods of modern ‘herbal practitioners’, William Withering too would have said something like “Oh my goodneſs!”

So Stephania, then

Let’s get back to where we started. The Belgian slimming clinic intended to dish out Stephania tetrandra. What’s the evidence that this does anything?

The first and most obvious question anyone should surely ask if offered “Stephania” is naturally “Does this contain Aristolochia by mistake?” The second is “How did you make sure it doesn’t?” Once on dialysis, twice shy.

But under the somewhat speculative assumption we’re dealing with the right plant, let’s move on. Just in PubMed, we’ll encounter dozens of articles. Many glow about the potential benefits of consuming Stephania. Take this quote:

Stephania tetrandra … , a traditional Chinese medicine, has demonstrated significant value in the prevention and treatment of [diabetic kidney disease] due to its active components.

There may be a few issues. This was published in the potentially predatory Frontiers stable of journals. Putting this aside, the authors seem to claim both therapeutic and preventative value! So how do they back this up? With well designed, controlled clinical studies? Naah. They refer to mouse studies of complex combinations of substances, and a review that doesn’t even mention Stephania. We also learn that:

It has a bitter and cold nature and is used to dispel wind-dampness, promote the flow of qi and blood, and promote diuresis and reduce swelling. Due to its diuretic properties, S. tetrandra is widely used in TCM formulas for the treatment of chronic kidney disease.

This does not inspire confidence. But perhaps there are clinical studies? I found one —a 2004 uncontrolled study of the white blood cell count in rheumatoid arthritis. Meh. But perhaps there’s more on components like tetrandrine and sinomenine?

In fact, there are a few clinical trials of tetrandrine in PubMed.6 About a decade ago, there seems to have been a burst of enthusiasm in the Chinese literature (a few small studies) for treatment of silicosis; it turns out that tetrandrine is also a calcium channel blocker, and it was studied for possible effects on portal hypertension in 1995, and compared to verapamil (for supraventricular tachycardia) in 1990. There are even fewer studies of sinomenine, as a possible anti-inflammatory in rheumatoid arthritis.

“It’s a feature”

So, some components of Stephania may (perhaps) be useful as an anti-inflammatory or calcium channel blocker. But in Belgium in 1990, it was being given (or intended to be given) as a ‘slimming aid’.7 Perhaps it was being used as a diuretic, to give the appearance of weight loss?

There’s one more observation worth making. A common theme in many of the papers that espouse the virtue of Stephania is the absence of any mention of toxicity! You’ll recall that William Withering went to great lengths to mention how Foxglove killed turkeys and poisoned people.

So where’s the toxicity data? I managed to find a review that examines this. Noting that S. tetrandra contains 67 alkaloids and 5 non-alkaloids, they describe “toxic effects in the kidneys and liver” based on one rat study. Which of the 30 bisbenzyltetrahydroisoquinolines is causing trouble? Or is it one of the 15 aporphines? Or something else?

Herbs with therapeutic effects are not there for your health. The substances they contain are often produced by plants to ward off, suppress or kill other organisms in ways that would make a Borgia blush. Natural history is a bloodstained story scrawled in dangerous chemicals. We have discovered that sometimes, in certain conditions, some substances can be used very carefully, and have therapeutic effects. But get the substance or even the dose wrong, and terrible things can happen.

Traditional medicines thrive on the concept that they combine a multiplicity of different components, often with many sub-components. In modern pharmacology, we shy away from this sort of stuff, because we know that none of these substances is included in a plant for the sake of kindness. The plant is generally out to get you. With careful judgement and a bit of initial luck, you may identify a single component where the toxicity is balanced by a beneficial effect in certain, special circumstances. To dream that some magical synergy will just emerge, especially with unmeasured variation in components, is lunacy.

In future posts we’ll discover that, where we combine even two or three drugs, we need to understand them all very well, and also have our thinking caps on.

Now, if someone offered you some ‘Stephania’,8 would you take it?

My 2c, Dr Jo.

⌘ This symbol indicates a link to one of my other posts.

In my next post, we’ll go radioactive!

He and Erasmus had more than a bit of a scrap about this publication.

True students of orthography may not forgive me for the way I’ve rendered the ct ligature here, but there is no kosher UTF-8 character for this!

The sodium-potassium ATPase pump. Although we’re coming to realise that a lot of the beneficial effects of digoxin seem to be related to modulation of tone in the vagus nerve, rather than direct effects on the heart. Pharmacology is never simple.

It’s very possible that hunters in Southern Africa were using poisoned arrows over 50,000 years ago. Analyses of more recent (7 kya) artefacts show mixtures of cardiac glycosides.

Technically, this is aristolochic acid I, and the main metabolite is aristolactam 1a.

I’m fairly sure that someone will point to one or more non-PubMed trials and enthuse about them. I’m not trying to be exhaustive here. Show me more toxicology data first.

Sadly, I suspect that if there was thinking going on at all, it was likely along the lines of “Herbs. Chinese herbs. Gotta be good.”

Or ‘Stevia’, from Walter White?

As a Yank, I have long believed that my country’s government has no legitimate authority to tell people what substances they can put into their own bodies.

But I have also long believed that there’s an excellent reason for strict and clear regulation about what substances others can sell for profit with the implication that OTHERS should put them into their bodies.

It’s amazing to me that the USA is maintaining our massive war on drug users while permitting cranks and quacks to become extremely wealthy marketing who-knows-what simply by claiming their products are not intended to treat any disease.

Why is that OK for someone like Doc Oz or Alex Jones but not for Eddie the crack dealer?

Good article! Given my background, I really appreciate the detail. The herb I researched promoted cell growth rather remarkably, but you can imagine where large doses of the herb led. I won’t name it, in case someone is stupid enough to dose themselves or others. It’s banned for human consumption in the UK and the EU.