Fermi and the Homeopaths

Quackery Exploded: Part I

“... organisers were forced to suspend the exhibit of Dutch artist Florentijn Hofman’s giant bath-toy replica, after powerful winds caused the duck’s rear end to burst while it was being re-inflated on Friday morning”

Fermi, sorted

In 1950, Edward Teller, Herbert York, Emil Konopinski and Enrico Fermi walked into a bar. Fermi said “Where is everybody?”

Yep. That’s the punchline, I’m afraid. The lame idea people latched onto is this: Because the universe is so big and has been around for so long, intelligence should be evident everywhere. The ‘Fermi paradox’. We should be visited often by UFO-steering aliens, aliens not simply content with selectively abducting the rural mentally ill; the spaceways should be criss-crossed by obvious signals of superintelligence. Whatever that is.

Putting aside the Anthropic Dog Conundrum (“Would we even recognise an alien intelligence if it bit us on the arse?”) and the idea that any truly smart alien intelligence would (a) be smart enough not to flaunt its intellectual wealth; and (b) likely have worked out that modulating the output of stars by building Dyson swarms around them (etc.) is showy and ecologically unsound, it should be obvious that if there is alien intelligence out there, they would not need more than a brief glance before they started instituting rigorously compassionate quarantining procedures to ensure our particular brand of stupid doesn’t escape the solar system.

For example, ET need no more than glance at the worldwide COVID-19 response,1 to conclude “They’re all fucking nuts”, and take suitable measures.

But if there were residual doubt, examination of how eagerly humans embrace quackery would utterly convince them that we are not playing with a full deck of science flash cards. That, and how we’ve unthinkingly embraced Dyson spheres in semi-serious science fiction.

“Hey, that’s unfair”

I have a huge soft spot for physicist Angela Collier. Take her recent 53 minute YouTube on Dyson Spheres. I’m sure you’ve heard of them. “Hypothetical megastructures that encompass entire stars, allowing an advanced civilisation to capture a large part of the power output”. Put forward by the brilliant Freeman Dyson.

I’m fine with the fact that she takes over half of this extended video to get to the punchline, because it’s so good when she gets there! Something I’d completely missed. And all the while putting the boot into Sam Altman, who seems so lacking in insight about both physics and engineering that he speculated about building an actual Dyson sphere!

I’m not going to give her game away. Yet. I will reveal her punchline at the end of my post, but first I’ll give you the opportunity to watch through. I did like the bit where Collier describes Altman’s Dyson sphere speculation:

It’s just a hilariously stupid thing to say!

But I’m sure that not a few viewers will choke up and cry ‘unfair’ or ‘elitist’ or even ‘he could be right’. As watching aliens giggle and smite their forehead equivalents.

Collier is just plain right. He is simply spouting daft bullshit as if it were true. The problem is that just as everyone is now a COVID-19 independent research expert, so everyone is expert at everything they’ve briefly googled. Including Dyson spheres.2 And we surely need to be quarantined by sympathetic aliens, because an awful lot of us won’t worry just a bit that if someone with a PhD in computational multi-scale dynamics is laughing and we’re not, we’re likely the butt of the joke.

The same sort of “Maybe I should ask whether I know more about the topic than someone who actually understands the maths” applies to pretty much the entire spectrum of human belief, especially when it comes to quack nostrums. Which brings us to the key differentiator between science and pseudoscience.

It’s not that some people are smart, and others are stupid, although it can help to have a good, thinking brain. The key is not even that some people have done a lot of relevant work, and others haven’t, although this too generally adds value.⌘ It’s more subtle.

The key

If you’re in a hurry, then you don’t need to read through my eventual dissection of nonsense nostrums, which will take several posts. All you need is this.

Quackery is clearly distinguished by the behaviour of its practitioners. Specifically, they simply will not try very hard to disprove their most cherished beliefs. If they seem to be trying, closer examination shows that even this is fake.

They never, ever properly Science it!⌘ If you present a well structured, science-based criticism of something like homeopathy, or Ayurvedic medicine, or crystal healing, or orgone energy, or some mysterious herbal remedy, then its proponents will double down, rather than sitting down and saying “Heck, I could be wrong”. But even before this, they will already have concentrated on justifying, rather than questioning their fervent beliefs. Doubt is something they can’t afford; but it is self-doubt that powers good science.⌘

So let’s look at a little science before we really get stuck in.

Not ready, yet

Around 1900, a large part of Ludwig Boltzmann’s distress3 came about when influential physicists like Ernst Mach and Wilhelm Ostwald pooh-poohed his theories. He had correctly developed statistical thermodynamics, which needs actual atoms and molecules to work. German philosophers and physicists were not big on them. We’ve already discovered Einstein’s 1905 paper on Brownian motion⌘ that takes molecules from the very theoretical to “Oh shit! They’re real, quite the most solid explanation”.

This is closely tied to the Avogadro constant: one mole of a substance contains 6.022×1023 molecules.4 Jean Perrin copped a Nobel prize in 1926 for working out “constante d’Avogadro.”

With some coarse assumptions about the average number of atoms in a star, the number of stars in a galaxy, and how many galaxies there are in the known universe, we can now calculate that there are likely a shade over 1080 atoms in the known universe.

Of course, we can still continue to question the Science (that’s how it works) but we’re on a firm enough footing to start exploring some unscience. We’ll ultimately discover that being out by a few orders of magnitude is not a biggie here.

Homeopathy: much ado about nothing

To understand homeopathy—insofar as we can begin to understand an idea that is based purely on post-hoc justification of quintessential unreason—we need to go back a bit.

Back to way before molecules. 1796. At the time, ‘physicians’ were pretty useless. Pharmacology was just getting started, courtesy of William Withering who wrote up digitalis in 1785, and died in 1799. But most of Medicine was bullshit, and Samuel Hahnemann could see this. So he came up with a different theory, “like cures like”, and did the best he could to test his ideas. We can’t blame him. Too much.

Hahnemann reasoned that if a poison replicated the symptoms of a disease, then itsy bitsy teensy weensy doses of the same could cure the disease.5 Subsequently, Science and Medicine have moved on—but homeopathy hasn’t. But where Hahnemann really lost it was in the extent of his dilutions. He took ‘doubling down’ to absurd lengths.

C this

Let’s introduce some homeopathic notation! Over multiple stages, Hahnemann would dilute something by a factor of 100. We’ll call the first such dilution “1C”.6 So 2C is taking 1C and diluting it one hundred fold, again. And so on. You can work out that after 12C, you end up with one part in 1024. From our knowledge of the Avogadro constant, if we start with a mole of something, after 12C there’s sod-all molecules left! But that’s nothing.

The ever-popular homeopathic ‘Oscillococcinum’ arose when French physician Joseph Roy misidentifying a supposed bacterium (‘oscillococcus’) in the blood of those with influenza. So the treatment of ‘flu was obvious to him: make up a 200C dilution of pre-rotted duck offal as a cure for this viral infection (and pretty much everything else, including tuberculosis, gonorrhoea and ‘cancer’). How many mistakes can you spot here?

Translated, 200C is one in 10400. In other words, do as follows:

Take all the atoms in the known universe. Dilute to 40C. That leaves you with—about one atom. Take this atom, and replace it with an entire universe. Dilute as before. Take the remaining atom. Replace it with an entire universe. Dilute again. Take the remaining atom, replace, and dilute. One more time, with feeling. Done.

Can you see how supra-astronomically ludicrous this all is? But I’d suggest it provides an approximate measure of the Bayesian priors related to homeopathic dilutions. If we start with a mole of something, and 200C it, the odds appear to be no better than 1:10376—provided we accept things like modern atomic theory. But perhaps there’s an out?

‘Water memory’

Homeopaths proposed one. Not only do they dilute. They also whack their water between dilutions, claiming that this ‘succussion’ preserves or even enhances the efficacy of the remedy.

And here’s the thing. In 1988 Jacques Benveniste and his co-workers managed to get an article published in the prestigious journal Nature, claiming something that looked very much like ‘water memory’—immune reactions with ridiculous dilutions of 60C. The authors claim that vigorous shaking allowed “transmission of the biological information [that] could be related to the molecular organization of water.” Nature will still sell this shameful offering to you for a mere €39.95.

I call it ‘shameful’ for several reasons. Perhaps the least reason is because it’s never been replicated properly. It’s shameful because Nature is still making money out of what was effectively a publicity stunt that predictably backfired. A condition of publication was that the results then had to be tested in independent laboratories, and that a follow-up team examined the lab.

Subsequently, everything was predictable too: of course the results weren’t replicable, and of course the investigators found unreliable techniques, and of course Benveniste then cried ‘foul’, describing the investigation as “an ordeal”—and of course true believers conclude that scientists | the cabal that secretly runs the world | alien reptiloids have deliberately produced negative results to maintain the New World Order | Socialists | Freemasons | Elders of Zion | One-eyed Rasta Libertarians, or whatever. Pick your conspiracy.

But there’s something more we can learn here, and it’s fundamental.

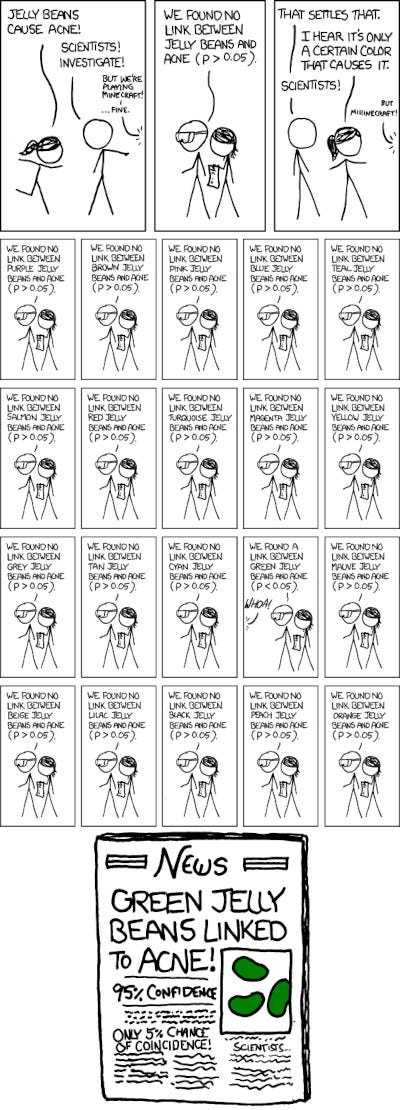

p-smoking

At the end of the day, people who believe in homeopathic remedies will not only continue to purvey and use them. They will continue to make claims of efficacy in clinical settings. And if I go to PubMed and search for the word ‘homeopathic’, I obtain eleven thousand articles. Of these, 320 are “randomised controlled trials”.

Now let’s step back and think about this for a moment. Many of these will use a ‘p value’ of about 0.05. That is, we first establish a “null hypothesis” that the control treatment and the intervention are no different. If statistical evaluation of the results shows that (surprise!) the two treatments appear to differ at this 0.05 “level of significance”, we reject the null hypothesis at this level.

But what does this mean? There is wide misunderstanding. Quite often, people make the mistake of suggesting silly things like “We’re 95% sure this didn’t occur by chance” or “there are important differences between the control and the intervention”. Errors like this are so common that the term ‘p-value fallacy’ has even been invented to encompass them.

The p value does not establish any sort of probability that a hypothesis is true. And by the very nature of the threshold we’ve set, if we repeatedly compare two treatments that are actually identical, through pure random variation we’ll sometimes obtain a false positive, a “Type I error”. This depends on the precise circumstances, but such errors are remarkably common, and far greater than 5%. David Colquhoun7 neatly and rather brilliantly fleshes this out:

If you use p=0.05 to suggest that you have made a discovery, you will be wrong at least 30% of the time. [My emphasis]

There is also no glib way of translating a p-value into something useful to a Bayesian.

Pointless

We know from our simple Bayes tutorial⌘ that with likelihood ratio LR:

Posterior odds = LR × prior odds

We can state this clearly for our two models M1 and M2, and our data D:

LR is the likelihood ratio. But is it even possible to somehow translate p-values into this environment? There are two fun ideas here. First, we can broadly set some limits on the LR, given the p value. Second, we can examine the ‘likely’ priors of, say, homeopaths and skeptical scientists, and slot them in. Both approaches are educational, so let’s do this.

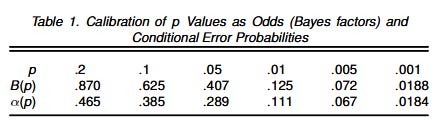

In 2001, Thomas Sellke and colleagues published a paper called Calibration of p Values for Testing Precise Null Hypotheses. This is worth a read. At this point though, I’d suggest that if a little maths makes you break out in hives, you may wish to either skip to the next section header, or first take a non-sedating antihistamine.

First, the authors explore a model, here the null hypothesis (H0), more formally:

Our theoretical model here is the continuous density distribution f(x). We have our observed data xobs, and we choose a statistic T(X) that lets us compare how the model fits with the observed data. The bigger T(X), the more incompatible the data are with the model. We can even define p:

T() will commonly represent something like a Chi-square test. Skipping over some small but important details fleshed out in the actual article, we can compute the lower bound of the Bayes factor (LR) as follows:

Their Table 1 provides values for B(p) which you can also easily work out for yourself:

The important take-away here is that these LR values aren’t that small.

Different priors for different folks

How sure are you that your basics are solid? Don’t answer 100%, ‘cos that’s silly. In Science, we know that we’re never sure—in fact, we can argue that in the bigger scheme of things, all of our theories have a zero probability of being ‘true’, but we can still use Bayes to compare theories. And here, our priors for things, like homeopathy, that just don’t join up are pretty small.

From above, we can put an upper bound on the credibility of say a C60 dilution: the odds of there being even one molecule left. It’s this: 1:10(120−24). Assuming, well, molecules. The odds are 1:1096.

Now either we’re right, or adherents of homeopathy are. Perhaps we can find some common ground by ‘averaging out the two’? But if they say there’s a “million-to-one chance” they’re wrong, this vanishes when we put them up against ours.

To counterbalance our extreme odds, they would somehow have to justify saying they’re something like 99.999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999,999% sure they’re right. And doubtless, some will—but they simply don’t have the underlying theory to back this up.

In the face of this, a likelihood ratio of 0.407 or even 0.02 makes vanishingly little difference to any reasonable Bayesian calculation. There is just such a huge disparity between us and them, that it’s utterly pointless doing clinical studies at any ‘reasonable’ p threshold.8 The results will change nobody’s mind.

“At least it’s harmless”

The global homeopathic medicine treatment market was valued at US $ 9.3 billion in 2023. It is tempting to speculate how much good might have been done had this been spent on something else, for example food for hungry people, or medicines that actually do work. But perhaps we can reassure ourselves that, well, at least it was just water. Not so fast. One study found this:

We analyzed 134 homeopathic remedies and found high alcohol levels, insect and animal parts, carnivorous plants in alcohol, and toxic heavy metals. Classical dilutions had the highest alcohol content (median: 91.02% v/v). Highly diluted formulations of arsenic and mercury had detectable lead levels. Proprietary medicines also showed various potentially toxic bioactive plant compounds, heavy metal contaminants, industrial-grade solvents, and pharmaceutical intermediates, raising concerns about organ toxicity ...

Around the world, homeopathy-related deaths have been noted. After a few hundred years, it is surely time to put this peculiar practice in the grave. We might still learn something, though.

What can we really learn, then?

If my Aunt Martha had walked into a bar in Sydney, together with (say) Edward Teller, Herbert York and Emil Konopinski and said “Where the bloody hell is everybody?”, the most that could have happened is that (a) this pronouncement might have spawned a lot of really bad advertisements promoting Australia; and (b) sane people might have answered “New Zealand”. However, because Enrico Fermi said it, suddenly people started speculating wildly about aliens modulating the behaviour of stars. It was a passing question of little worth.

Now if you haven’t already watched Angela Collier’s Dyson sphere rant, this is your last chance. I’m about to reveal the punchline. Ready? Here goes ... Dyson’s paper on Dyson spheres was a joke. Dyson was taking the piss out of SETI, the Search for ExtraTerrestrial Intelligence.

A lot of people still haven’t got it! And yep, I didn’t see the humour either, until Collier explained it to me in small words I could understand. We need to learn that every pronouncement of a fabulous physicist like Fermi or Dyson doesn’t need to be taken seriously, every question analysed for Deeper Meaning.

And likewise, when we encounter something really silly, like Penrose banging on about qualia,⌘ or homeopaths diluting water and whacking it with a stick, we would be incredibly foolish to attach too much value. Specifically, it’s daft to run studies of homeopathy, with p-values and whatnot. Instead, just indicate how silly the whole thing is.

There is an argument that we should then simply leave silly people to take their silly remedies, but there’s an even darker side of ‘homeopathic’ remedies. They don’t make sense, they don’t work, but they do kill children. So what should we do?

What we shouldn’t do is publish homeopathic ‘studies’ in serious journals, or licence ‘Homeopaths’, as ways of giving them apparent credibility. Legitimising the practice seems astronomically stupid.

In contrast, it is surely appropriate for whole societies to step forward to prevent harm and waste in the obvious ways they can: stopping distribution of inefficacious nostrums that might be used therapeutically, holding people responsible for harm caused by components that should not be there, and mandating clear and accurate content descriptions:

“Contains just water, no active ingredient whatsoever”.

If people want to buy just water at inflated prices, that’s on them.

My 2c, Dr Jo.

⌘ This symbol indicates a past post of mine that will provide more detailed information.

My next post will build on the idea of stopping harm, using a pretty scary example of Herbal Healing gone wrong.

With the exception of my country,⌘ of course. Although the craven incompetence and abject cowardice of our current government would allow examining aliens to disregard this as a statistical blip.

And yes, I know, Anonymous 4Chan wankers will be all over the idea that “Altman is joking, and you just don’t get the joke”. If he were joking, it would be far more lame than even Fermi’s paradox.

And possibly even Boltzmann’s ultimate suicide in 1906, not helped by his bipolar affective disorder. It’s sadly unlikely that Boltzmann ever encountered Einstein’s paper, despite it being published a year before his death.

Now fixed in the SI system to exactly 6.022 140 76 ×1023 mol-1.

He might have been quite at home with something we’ve recently encountered⌘ in our exploration of life-prolonging nostrums: assertions that something like resveratrol, which increases oxidative stress, ‘bolsters your anti-oxidant defences’.

No human notation is ever straightforward, so in homeopathy, for C we also have CH and CK; there’s also X (or D), a one in 10 dilution. And there’s a 1:50,000 Q scale too.

Colquhoun makes a spirited argument in favour of not regarding anything over p < 0.001 as exciting. That’s 3 standard deviations. Physicists use 6 SD.

This does, of course, ask what sort of evidence we’d need for “water memory”. We would surely need an entire body of meticulously tested theory that demonstrates how a water molecule might retain and transfer information from, say, a protein molecule, in the face of the thermodynamic noise in a glass of water. Even six sigma might not cut it, here. It’s just so, well, Dyson sphere-ish.

Interesting article, thanks! I'm really looking forward to your next paper, however. Back in the early 1970s, when I was a medical biochemist, I wrote a dissertation for my studies. it was called "Testing the efficacy of a subset of herbal remedies and documenting their likely biochemical pathways". Quite eye-opening. And yes, I did find one that worked. It's now banned for human consumption in the UK, but it's routinely given to racehorses.

Thanks for the great post, of course, but also for the introduction to Angela Collier, who should be the mandatory bucket of cold water that accompanies every single thing Musk, Altman, Thiel and their fellow tech bro ilk actually say out loud… ;)