Adams’ Puddle

(To hunt down intelligence, let's probe our own stupidity!)

i met a toad the other day by the name of warty bliggens he was sitting under a toadstool feeling contented he explained that when the cosmos was created that toadstool was especially planned for his personal shelter from sun and rain thought out and prepared for him

(Don Marquis, Archy and Mehitabel 1927)

Sometimes we are so silly that satirical poetry is necessary. This applies to a lot of what we’ve written about ‘intelligence’. Let’s explore. We’ve already established that fixating on IQ is quite, quite daft, so let’s cast our net more widely.

This isn’t easy. The American Psychological Association wring their hands for 24 pages trying to define intelligence. Their overview touches on overcoming obstacles, adapting to the environment, learning from experience and ‘understanding complex ideas’. They then blather on about IQ, The Bell Curve and whatnot; so let’s instead focus on those first few ideas.

In the following we’ll establish where intelligence comes from (motor chauvinism), ask the birds, find out how to steal a free lunch, look for a single way to categorically identify human smarts, examine abuse of the word ‘conscious’, bump into the third level of Pearl’s ladder in a most unexpected place, and tie these into a reasonable definition of ‘intelligence’. Promise.

Motor chauvinism

There may be about as many definitions of ‘intelligence’ as there are academics researching it; but most of these seem to boil down to getting stuff done. This is as practical as surviving in the Kalahari desert or in a dangerous favela in Brazil, or as abstract as playing the theremin really well, or proving a theorem in algebraic geometry to the satisfaction of your peers. And things become really interesting when we move outside our own narrowly human view of how things work.

Perhaps a good starting point is the answer to the question “Why do we have brains, anyway?” I believe nobody has answered this better than Daniel Wolpert, Professor of Neuroscience at Columbia University. He and his colleagues have recently provided sophisticated models of context-dependent learning, but ages ago I was taken by his confession that he is a “movement chauvinist”. He provides the potent argument that the reason why we have brains is to control movement. Natural selection favours predictive abilities (à la Bayes) because to control, we need to predict.

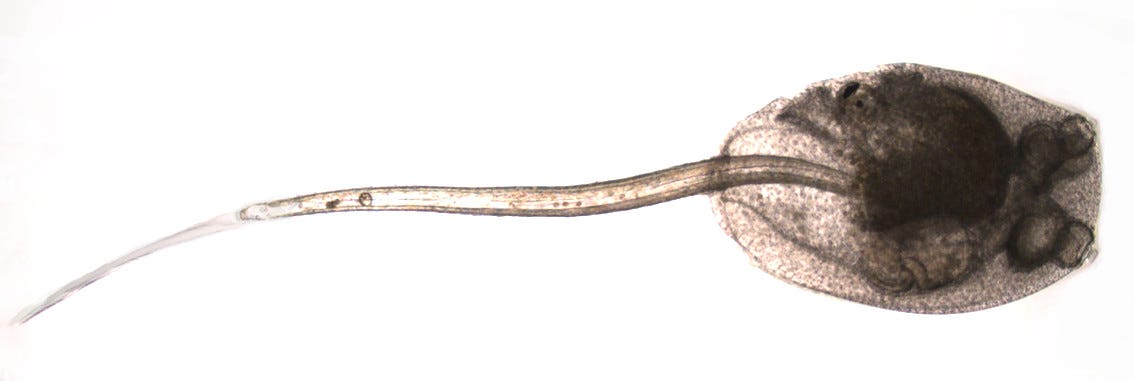

I love his tale of the sea squirt. The larva of the sea squirt is a highly motile tadpole-like organism with a neat little brain, pictured above. Once it settles down on a rock, and transforms itself into an adult, never to move again, the first thing it does is digest its own brain!1

Where did I leave my keys?

Speaking of Bayesian, we already established that pigeons are smarter than undergraduates, at least when it comes to the Bayesian logic required for the Monty Hall problem. There are many other examples of avian smarts.

Take Clark’s nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana). This small, solitary crow survives the winter on its spatial memory. It has a pouch under its tongue that accommodates over fifty pine nuts; it stores a pile at a time in thousands of separate caches.2 The bird will remember the position of pretty much every cache, even when buried in snow!

But that’s a fairly specialised ability.3 Testing using a ‘swipe left/swipe right’ approach has shown that Clark’s nutcracker can ‘only’ remember about 500 distinct pictures: fewer than the 800 that pigeons manage! The existence of specialised smarts does however lead us into an important idea from informatics…

Make your own Free Lunch

TANSTAAFL— “There ain’t no such thing as (a) free lunch” was popularised in Robert A Heinlein’s The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. The term is said to date back to a 1938 fable in the El Paso Herald-Post, where a king serially executes economists for being too long-winded. The last one left standing mutters eight words.

“No Free Lunch” (NFL) also refers to a bunch of theorems by a different Wolpert (David), and William Macready. The general theme is this:

... for any algorithm, any elevated performance over one class of problems is offset by performance over another class.

If we’re looking for ‘general intelligence’ that performs equally well over all tasks, then there will always be other intelligences that do better in some of these domains. We already know that anyone who claims their brain is superior at every task is in for a rude shock—usually one provided by a child with a serious expression.

And it gets worse. As W&M explain:

Roughly speaking, we show that for both static and time-dependent optimization problems, the average performance of any pair of algorithms across all possible problems is identical.

Overall, you can do no better than random! There are several get-out-of-jail cards, of course. The main one is when we’re applying ‘intelligence’, it’s never generalised over the whole space of possibilities. We always have a context, and specific domains that are more interesting than others. We have Bayesian priors.

Better still, with evolution over time (internal refinement of algorithms, with selection of a ‘champion’—termed “self-play”), there are free lunches! Co-evolutionary ‘arms races’ allow selection of efficient algorithms.4

But NFL is still a bit humbling. Not that this has stopped us in the past.

Uniquely human

Many people are aware of the Weak and Strong Anthropic Principles. The Weak One says, basically, that it was jolly amazing of the universe to be constructed in such a way that humans could evolve to a point where they make a living in, for example, universities, while the Strong One says that, on the contrary, the whole point of the universe was that humans should not only work in universities but also write for huge sums books with words like "Cosmic" and "Chaos" in the titles …

The UU Professor of Anthropics had developed the Special and Inevitable Anthropic Principle, which was that the entire reason for the existence of the universe was the eventual evolution of the UU Professor of Anthropics. But this was only a formal statement of the theory which absolutely everyone, with only some minor details of a "Fill in name here" nature, secretly believes to be true.

(Terry Pratchett, Hogfather 1996)

The main defining characteristic of human intelligence seems to be arrogance. This applies particularly to an important component: memory. We’ve classified memory rather a lot: implicit and explicit memories, and within the latter, semantic memory (related to general patterns) and episodic memory (for specific episodes).

Arrogant specimens of Homo sapiens even put up the “Bischof-Köhler hypothesis”, that non-human animals can’t possibly have episodic memories. This seems dodgy. If you’re trying to ask the animal to relate their recollection, I’d imagine you first need to demonstrate your fluency in speaking orca or vervet monkey. In any case, we’ve already met birds that recall precisely “what, where and when” they stored. The California scrub jay even plans for the future; monkeys do fine here.

It seems that to encode and retrieve past experiences, we need a functioning medial temporal lobe (with the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped structure intimately involved in memory). Isn’t it quite daft just to assume that animals that have these structures can’t form useful episodic memories? Maybe other animals like orcas indulge in similar speculation about us. Or perhaps they’re smarter than this.

Conscious?

We’ve also abused the word ‘consciousness’ no end. Dictionaries commonly define the word along the lines of being “awake, aware, or able to think”. This fits with physiology. If something can be anaesthetised, then the state that it’s in is ‘unconscious’, and the un-anaesthetised state of the normal organism is ‘conscious’.

We can anaesthetise fruit flies, with under a million neurones. We can even anaesthetise nematode worms like Caenorhabditidis elegans, with its 302 neurones. Unfortunately, humans have equated ‘consciousness’ to many other things, including ‘mind’, ‘introspection’, ‘self-awareness’ and so on. From now on, I’ll refer to consciousness as the anaesthetic-free form, and we’ll identify other terms for other concepts and states.

Fortunately for us, we’ve already dispensed with qualia, and how your perception of the colour red is unique to you, so we don’t need to revisit that tired ground. We’ve met religious pigeons. We’ve even addressed free will and explored causality in the context of directed acyclic graphs. In the same post, we explained how reinforcement learning is causal and volitional, and distinct from classical conditioning. So we’ve covered a lot of the behaviour that organisms with brains display; we have a reasoned approach to volition and causal reasoning. None of this is uniquely human.

Sentient and sapient?

There’s a bunch of other terms, though. Let’s start with introspection. As the word suggests, it refers to “looking in”, that is, looking into oneself. This could become confusing, were we not already aware that people and rats have inner models of other people and other rats. It’s not difficult to work out that having access to an inner model of yourself is a given.5

Closely related are ‘feelings’. There are two convenient components here. The one is that we can observe emotions like rage, fear and affection in animals; the other is that we can talk about similar emotions in ourselves.6 We know that the limbic system mediates these responses, which clearly have value. Confront an animal, and it will generally do the sensible thing and flee, unless it has a strong perception of superiority, or views you as a food item. Trap the animal, and back-to-the wall it will often attack vigorously, especially if defending its young. This is a primitive and valuable response.

As expected, we humans have added our own special tests to show how convincingly special we are. For example, there’s the rather daft “mirror test”, where we test whether an animal responds to some specific feature when seeing themselves in a mirror—effectively selecting out those animals with good vision that have a clear visual image of ‘how they look’ and can be bothered to signal this in an unambiguous way that humans understand.7

We should touch on ‘sentience’ too, which is simply the ability to feel. The archetype here is feeling pain, which is common to most organisms which have nervous systems, simply because there is an advantage to being aware of and responding aversively to bodily damage, or stimuli that go along with such damage. Of course “fish feel pain”; they have the required wiring, and respond appropriately. This is covered by the Cambridge Declaration. We’ve grown up a bit here. Just a few decades ago, premature babies were operated on without adequate pain relief, because ignorant doctors thought they couldn’t feel pain.

But here’s one more thing (from The Fairness Field Guide), and it’s subtle in its implications:

Pearl beyond price

In a previous post I explored Pearl’s do() calculus. This is part of his causal hierarchy, pictured above. There are three, increasing levels of complexity as we climb his ladder (or the staircase above):

Seeing: The level of association.

Doing: The level of causality—the do() calculus we’ve already noted, in the context of directed acyclic graphs and Bayesian thinking.

Imagining: Counterfactuals.

The slightly tricky bit is that you can’t “do” level 2 on level 1, or level 3 on level 2. We’ve spent some time looking at aspects of the do() calculus, but haven’t extended the same courtesy to counterfactuals. The basic idea here is evaluation of alternative realities that might happen, or might have happened. Some people will of course assert that this is solely a sophisticated human thing.

So let’s explore a counterexample. We won’t even choose a vertebrate! As Marco Facchin and Giulia Leonetti determine in their article Extended animal cognition, the tiny jumping spider Portia fimbriata is second only to humans in its hunting strategies. She is expert at camouflaging her movements and builds strategic webs. She tweaks the webs of prey spiders to resemble a trapped insect. She can devote an hour of planning and exploration to take down dangerous prey. Strategies include continuing to pursue prey even when it’s out of sight and abseiling down to bite prey from behind. She combines everything her tiny brain (just 600,000 neurones) can bring to bear, using her entire body as a tool for exploration and hunting.8 Portia effectively explores and reject possible hypotheses as part of her pursuit of prey! I’d firmly suggest this is “Pearl level 3”, although not everyone will agree.

We can learn something else from Portia. Just because something is small, doesn’t mean that it’s inferior. Often—especially with arthropods—it’s simply more finely tuned to a specific set of tasks. Often that task is finding lunch. Without dying.

Image of Portia fimbriata.

Anthropomorphic v anthropocentric

“This is rather as if you imagine a puddle waking up one morning and thinking, 'This is an interesting world I find myself in — an interesting hole I find myself in — fits me rather neatly, doesn't it? In fact it fits me staggeringly well, must have been made to have me in it!' This is such a powerful idea that as the sun rises in the sky and the air heats up and as, gradually, the puddle gets smaller and smaller, frantically hanging on to the notion that everything's going to be alright, because this world was meant to have him in it, was built to have him in it; so the moment he disappears catches him rather by surprise.”

(Douglas Adams, The Salmon of Doubt 2002)

It should be fairly obvious that in trying to make ourselves special, we’ve missed a few tricks in the bridge game.9 We’ve also neglected a principle that I established some posts ago: start from a position of similarity. It’s not hugely surprising that human and other brains have similar operating principles. After all, we share much of our DNA with other animals—especially where it comes to general themes—and we share the same biosphere. We often also share similar brain structures, and even when we don’t (e.g. Portia) the constraints that are imposed upon us often shape our behaviour through processes like natural selection.

Above, we’ve witnessed the erosion of many things that have previously been considered qualitatively (categorically) special about humans. In past decades and centuries, the second-greatest crime10 academics could accuse you of was ‘anthropomorphism’—attaching ‘human’ characteristics to non-human animals. We can now see that this is a really stupid non-crime. The actual crime is to ignore the overwhelming wealth of ways in which we are similar to other animals.

And if you tell me that you’re ‘sentient’, or ‘sapient’ or ‘self-aware’, how can I trust you? You might be lying, or simply a bit confused. You can see that the same strictures apply to your own appreciation of yourself. We need something more.

As usual, though, there is no need to despair. We can accept something like ‘self-awareness’ or ‘ability to function at Pearl’s level 3’ as a hypothesis to test in the real world. Once we start doing this—in context—we’re hoppin’! Or jumping, as the case may be.

It seems reasonable to conclude that when we’re dealing with the multitude of labels associated with ‘intelligence’, most of the time we should be interested in degree rather than ‘nature’. We should be talking quantitative rather than qualitative!

Of course, another major obstacle in the past has been the idea that we have some sort of special ‘soul’. Fortunately, we’ve already cast that strange idea aside.

What is ‘intelligence’, then?

In my very first post, I explored how to do good Science: start with problems, propose tentative explanatory models, and test these both logically and in the real world. Most models will fail; but even those succeed are open to continual re-evaluation, as they cannot be ‘true’. We now have the further implication that we are working on Pearl’s level 3, reasoning with counterfactuals. Reasoning must also be in context, or we tend to bump into the NFL problem.

We can now see that ‘intelligence’ is the ability to produce solutions to problems in reality, using all three of Pearl’s levels of reasoning. This is a reasonable pre-requisite! It also seems to be sufficient. ‘Even’ Portia is capable here. But what about machines?

Next, we’ll start looking at artificial intelligence (AI), together with the myths and confused ideas we’ve fashioned around it. Many problems arise from the misunderstandings mentioned above, but there are others. My first AI post will be “How much does a thought cost?”

My 2c, Dr Jo.

Topmost image was generated by Ideogram “A rather twee photograph of warty bliggens the toad, sitting under a toadstool made specially for him by the creator of the universe”.

“Like academics who gain tenure.” Given his other work, we can likely even forgive Wolpert for providing consulting services to Meta. I wrote the above post and then re-watched his TED presentation after a 10-year gap, and it was only then that I realised the profound effect he’d had on my thinking.

Whitebark pine seeds have more calories per gram than chocolate does.

Other crows however have even more remarkable cognitive skills: they can make tools and recognise individual humans (especially those who kill crows) years later.

The key idea here is that if the class of games is closed under permutation, then NFL still applies for any two algorithms e.g. https://nips.cc/media/neurips-2024/Slides/95414.pdf ; some setups still fit NFL despite not being closed under permutation: “focused sets”.

We will reserve our discussion of how this might work for a later AI-related post.

Rats laugh and play; this too deserves its own post.

So far, great apes, some dolphins, pigeons, European magpies and elephants have acquired the human stamp of approval here, but why humans consider this important is quite opaque. People sometimes use words like ‘sapient’ here, but I suspect this is just another “I’m special” paraphrase.

Portia fimbriata needs these strategies to survive. Its main prey is other spiders; in fact, some populations like that in Queensland specialise in hunting other jumping spiders! Another refinement is that unlike other species, P. fimbriata females don’t eat their mates, and in fact a sub-adult female may share the same nest with a male until she finishes her final moult, after which they copulate. The stories and studies around Portia make for an abundant and astonishing read. Try this overview: “being innate does not mean inflexible or non-intelligent”.

As my mother in law always emphasises, the key idea in playing bridge is building a bridge.

The greatest academic crime always seems to be plagiarism, rather than, say, ignoring genocides, or denying genocides, or promoting bigotry, or making shit up; or indeed, elevating people to an undeservedly lofty position in some sort of arbitrary hierarchy.

Fascinating discussion on a topic I've spent time on since at least being told in a college class for would be teachers that IQ test really only manage to test how well you do IQ tests.

My simplistic definition of intelligence: the ability to learn a new task. One of my examples was pointing out that I had a cat whose relative ability to catch small rodents w/o tools was genius level compared to my (& her Ferdinand the Bull personality son's) ability to do the same.

I'm a philosophical (transcendental?) idealist. My conclusion is that the four (five, two?) fundamental forces described in physics arise from a more fundamental “field of energy” that manifests, when expressed through sufficiently complex structures, the characteristics we associate with (in humans) consciousness. An extension of Assembly Theory if you like.

The purpose being to answer the question (who, what, where) am I?

And yeah, orcas are clearly more intelligent than humans but lacking thumbs (& a dry environment that is more conducive to not dissolving everything in it) they are far less preoccupied with manipulating their environment than with comprehending it (a task for which their sonar & 0.5Hz -120kHz auditory range is far better suited).

Thank you for this post.

So it seems you’re making the point that intelligence is helpful to the main purposes of life as we know it, which are survival and self-propagation…? But the primary reason AI has been developed isn’t to accomplish either of these things, is it?