I have recently relished pretty much every episode of the American sitcom Ghosts. A guilty pleasure, where one can enjoy the hilarious interactions between a thousand-year-old Viking (who hates the Danes), a slightly but perpetually stoned 1960’s hippie, a Lenape hunter who died in 1513, the closeted gay Continental Army officer Isaac Higgintoot and the straight-laced lady of the manor Henrietta Woodstone, who has now discovered the joy of washing machines. And let’s not forget Pete, Trevor and Alberta.

But I’ve just cheated you. That intro was designed to catch you off guard. The main source of humour in Ghosts is the contrast between Sam—who can see the ghosts—and her husband Jay, who can’t. For me, the slightly distressing point that I’ll soon explore is that in the early 21st century, there are still some who would accept the whole scenario as only fractionally removed from reality. People who really believe in an ‘afterlife’ and all or at least some of its trappings— spirits, ghosts, the persistence of dead souls and so on. Perhaps half of humanity will become irate at some point during my post.

I must also warn you about two things. Necessarily, this will be a long post. But more important is the fact that what follows may be extraordinarily distressing to a number of people: those who are afraid of death; anyone whose stomach turns at the thought of vivisection; and indeed, those with firm faith in souls or the afterlife. If you are one of these people, please think carefully before you read further. We’ll start gently, though. Before we go back nearly two millennia, let’s take a slight jump back to the 1930s.

Otfrid Foerster and provenance

To this day, if you look up the Wikipedia entry on Otfrid Foerster, you’ll read a piece that praises his contribution to neurology. A brain surgeon who innovated, attempted surgical cures for epilepsy and, most important of all, mapped the dermatomes (We’ll come back to this in a moment). We read:

Described by his biographers as a giant of neurosurgery, a man of towering intelligence, kindness and charm, he commanded several languages fluently and was a prolific lecturer and writer, having published more than 300 papers and several books.

Unfortunately, this is the sanitised version. Or, to quote Poker Face, my current favourite American serial, “Bullshit!”.

Otfrid Foerster operated in Germany in the 1930s. It’s not clear whether he was much of a Nazi,1 but it now seems apparent that several things he did might have made at least some Nazis blush.

People who assisted him at his operations describe his savagery. And, although his original records seem to have vanished, it’s crystal clear that he took vulnerable people and unnecessarily cut all but one of the surrounding nerves as they came off the spinal cord, so that he could map out which portion of the skin (dermatome) the remaining nerve supplied with sensation.2

We use Foerster’s dermatome maps today to identify which nerve is not working well if the skin there is numb or sore. I don’t know whether or not the small papier mâché model pictured above did,3 but other, more conventional charts surely do. And what you won’t see is any sort of disclaimer, along the lines of:

This dermatome map was heavily based on the work of Otfrid Foerster, who likely abused the patients under his care to obtain the information presented. It’s also inaccurate, because there’s a lot of variation, and dermatomes overlap.

I’d suggest that we can learn several lessons from this little digression. Foerster had no problems with publishing his dermatomal findings in a reputable academic journal. Today, one would hope that Brain would be a bit more picky about Foerster’s ‘informed consent’ and methodology. We ourselves need to be honest about dodgy sources, and whether what we say it is accurate, or lies to children.

But above all we can see that, even if we go back less than a century, the medical establishment as a whole had a very different mindset.4 It’s difficult to “get into the minds of people at the time”. Or, if we can, we may not like what we find.

Aelius Galenus

Galen, as we now know him, presents similar problems. Things seem progressively more difficult the further back we go.

Born the son of a rich Greek architect in 129 CE, Galen was a remarkable man in every way. He lived to the very ripe old age of about eighty, and during his time witnessed the Antonine Plague (AKA “the Plague of Galen”) between 165 and 180 CE, now generally believed to have been smallpox. It’s estimated that at least ten percent of the population of the Roman empire succumbed.

The reason why his name is attached to the plague alongside Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (the then emperor) is because Galen already had clout. He also wrote a fair bit about the plague—but in keeping with our recent observation about going back in time, his descriptions are irritatingly vague concerning actual clinical observations. He seems to have been more eager to describe what he did to plague victims.

Galen was a bit of a showman, you see. When his father died and left him well off, he extended his medical knowledge over a leisurely period of more than a decade, touring the Mediterranean and finding the very best teachers he could. Finally, he went to Rome, where he broke into the medical establishment in a big way, ending up as the personal physician to several emperors.

The way he established himself is interesting (if somewhat disturbing). Before Rome, he became doctor to a gladiatorial school in Pergamum, where he was exposed to and became skilful in managing all the severe injuries you might expect to see. He was an expert surgeon. When he got to Rome, his public demonstrations were popular. He would vivisect a live pig, which needless to say squealed in agony—until he cut the nerves to the larynx. As he explained to his audience, this shows how the brain controls the body by means of nerves.

Even more disturbing was his dissection of the brains of living Barbary apes. At this point, it’s easy to look away. It’s almost as easy to remark that these were different times, where bloody gladiatorial contests were flocked to by the general public. It’s more difficult to walk across the bloodied sand and pull something of use from what we read. Let’s try this, though. We’ve already done so with Foerster, after all.

Easy to criticise

Like all of us, Galen was mostly wrong. This is not surprising. If, in contrast, we seek what was remarkable about him, we need to understand three things: the tradition he was working in, the competition, and what he “got right” from a modern perspective. Let’s do this in order.

We don’t know how many millennia ago human beings started speculating about the human “operating system”—what makes us tick. It may well have been about the same time that religion became important, which is ages ago. But Roman civilisation at the time was marinated in Aristotle, Hippocrates, humours, and pneuma (air/spirit).

Humours were not seen simply as bodily fluids like the aqueous humour of the eye today, but something more vital. We don’t know quite who first dreamed them up, but the idea likely goes back to the Ancient Egyptians, or the Middle East, and seems fairly closely related to themes we see in Ayurvedic and Chinese medicine, especially concerning the elements of fire, air, earth, water and (sometimes) space/aether. Related humours were blood—ancient rituals and beliefs seem to gravitate towards this—as well as phlegm (not our modern term, but any whitish fluid!) and two flavours of bile (yellow and black, respectively from the liver and [!] the spleen). To this day we might occasionally talk of someone being sanguine (bloody) or melancholic (full of black bile).

Galen was a prolific author, and edged out the opposition by publishing hundreds of books. He seized upon “the balance of the humours” and promoted this so successfully that the idea persisted largely unchanged for well over a millennium. As did a lot of his other errors, for example his theories of the circulation. Ignoring the valves in the heart, he believed that blood created in the liver mixed with pneuma from the lungs (channelled by the pulmonary arteries, don’t ask) and then mysteriously went through invisible pores in the septum between the ventricles, to get to the left side of the heart.

The competition

But if we consider all of this a bit strange, things get a lot weirder when we look at what Galen was up against. There’s no doubt in my mind that were the ‘Methodists’5 of the day alive today, they’d all vote Trump, wear MAGA caps, and do their own Internet research. The anachronistic image at the start of my post was generated by ChatGPT along these lines.

The ‘Methodists’ saw no need to research or understand the underlying anatomy and physiology—like a modern Internet Researcher, they relied on what was ‘obvious’, and believed that the whole of medicine could be assimilated in six months. Another group, the Empiricists also regarded anatomy and physiology as passé, but for a different reason: they felt that all you needed to do was look at the symptoms of individual patients and their responses to treatment, perhaps confining their learning of anatomy to patients whose mishaps had opened them up for inspection. Who needs anatomy and physiology? There was a stew of other philosophers.

Pretty much everyone agreed on one thing, however. There must be some uniting principle (hegemonikon, ἡγεμονικόν) that ran the body, and clearly it was based on pneuma (πνεῦμα)—what we might today call ‘soul’, ‘spirit’ or perhaps élan vital. Passages in the body (like blood vessels) existed to allow the free flow of pneuma, and this mediated things like intelligence. This seemed obvious: the nasal passages and sinuses were close to the brain, and allowed the intelligence of the air to flow in. For them, a stroke was due to a blockage of the flow of psychic pneuma! Yep. I told you it was weird.

A modern take on Galen

So what can we pull out of this ancient rubble? Recently, I explored how Thomas Harvey stole Einstein’s brain. The reason why he carefully preserved the brain in celloidin before chopping it up is because fresh brains are very squishy. Galen must have been impressively skilled to open up the living brain of a monkey, clearly identify the four ventricles (fluid-filled spaces within the substance of the brain), then fiddle with the bottom part (the medulla) and still keep the animal alive for some time.

He also got a lot right, based on his studies. One of his big arguments with the Empiricists in particular was that he saw the brain as the source of the nerves and the spinal cord. Galen was an ‘encephalocentrist’ who saw the ‘soul’ as residing in the substance of the brain “where thoughts take place and memory is stored”. The Empiricists stuck to the heart as being the important ‘soul’ bit, and where the anatomy disagreed came up with the cunning argument that either (a) you weren’t interpreting the anatomy correctly, or (b) it changed when you opened it up.

Anyone who has dissected a corpse (in second year Medicine, I did so for an entire year) will appreciate that this is difficult stuff. I still have nightmares about finding all the cutaneous nerves, and the anatomy of the foot.6 I think we can cut Galen some slack when it comes to his apparent confusion among nerves and other structures like tendons; he still seems to have got a lot right. It is a bit unfortunate that he didn’t check to see which way the valves pointed in the heart, as we might then have had an effective understanding of the circulation a thousand years earlier.

Likewise he felt obliged to see the ventricles in the brain as a source of pneuma. Otherwise, he was remarkably close to obtaining an anatomical and neurophysiological substrate for the ‘psyche’, based in the brain. We can now do a lot better—but at the cost of sacrificing a wealth of bad assumptions. To prepare us for this task, let’s go back to the heart.

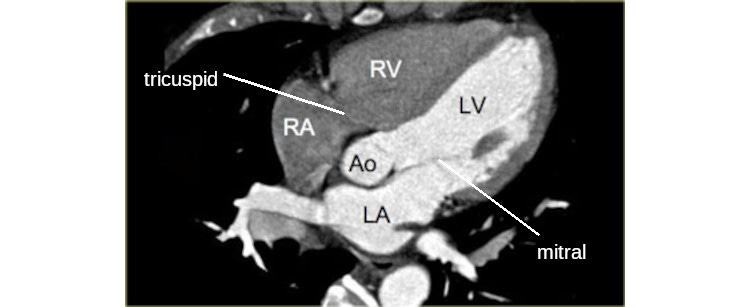

Modern ‘5-chamber’ view of the heart, showing the right heart (above, RA=right atrium and RV=right ventricle) and left heart, with the aorta and aortic valve in the middle. The tricuspid valve directs blood from RA to RV; the mitral valve, from LA to LV.

William Harvey

“I do not profess to learn and teach Anatomy from the axioms of Philosophers, but from Dissections and from the fabrick of Nature”

We should not confuse William Harvey (1578–1657) with Thomas, the brain thief from the twentieth century. William’s course was in some ways similar to that of Galen—his father was fairly wealthy and influential, and William had the opportunity to travel widely in France and Germany, learning anatomy from Fabricius, graduating in Medicine from the University of Padua, and eventually obtaining a Doctor of Medicine in Cambridge before becoming a member of the Royal College of Physicians in 1607, well over a decade after he started his BA. He ended up as the physician to James I and then Charles I. His key contribution was however published in 1628. His 72-page De Motu Cordis is the first properly joined-up model of the circulation of the blood. It’s still worth a read!

By means of careful examination and logical argument, he dispelled the myths established by Galen. Harvey looked carefully at the anatomy, and then moved on to function. He worked out that the pulsation of arteries depends on the contraction of the left ventricle; the right ventricle is there to move blood through the pulmonary arteries to the lungs.

Harvey did one more thing that was crucial. He did the numbers. Knowing the heart rate and the amount of blood ejected with each beat, he could estimate the amount of blood pumped every day. Galen asserted that the liver alone produced this vast amount of venous blood—which is obviously in error, once we have Harvey’s numbers (500 pounds of blood per day). He then did numerous, painstaking experiments on a large number of different animals (including embryos and transparent shrimps) to check his revolutionary theory that the blood circulated. He puzzled out how valves worked, not just in the heart but also within veins. And nevertheless, it took two decades for his meticulous work to overthrow the dogma of centuries. People were pissed off. And that was just the heart.

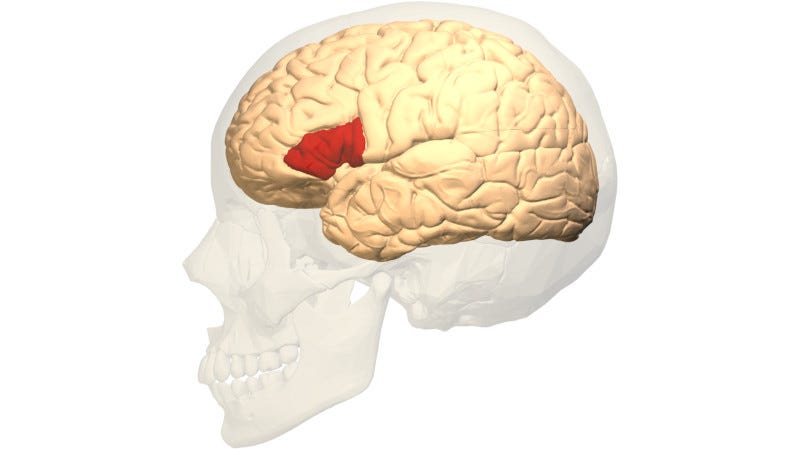

Picture of Broca’s area (here coloured red) in the brain.

Pneuma, today

As I observed at the start, many people around the world still embrace πνεῦμα in some form! They may call it ‘soul’, or ‘spirit’, or ‘atman’, or the reification ‘pure consciousness’. They may dress it in religious robes, or new-age mysticism. But the force is strong in them, it seems. Is this reasonable? Do we need7 this ‘auxiliary hypothesis’?

Today, our ‘mysteries’ are more contained than they were a few millennia, or even a few hundred years ago. Take the brain. There are still occasional surprises. For example, it was only in 2012 that the ‘glymphatic system’ was described in the brain—allowing cerebrospinal fluid to flow around blood vessels in the brain, pick up metabolic waste, and exit. We’re still arguing about the details.

But we’re pretty clear about how nerves and indeed brains work. We understand transmission of electrical impulses along the tiny processes (axons and dendrites) of nerve cells. We know a fortune about the vast array of chemical messengers that rapidly move across the gaps between nerve cells (synapses) and how they interact.

We also have a rich knowledge of the wiring of our enormous brains, with their 80 billion nerve cells and innumerable connections. We know a lot about how the brain joins up with the periphery (obviously not just Foerster’s contribution). We’ve worked out many of the mechanisms of sensory transduction too: when a sound, or a light impulse, or a touch on the skin stimulates the relevant cells, we now understand that this is translated into a set of impulses. Nothing remains of the ‘nature’ of that original stimulus; there’s just encoded information for the brain to work on.8

Starting in about 1850 with Broca, we also worked out that specific parts of the cortex of the brain are involved in specific functions, for example an injury to or stroke affecting Broca’s area will generally impede your ability to speak.9 Poke the temporal lobe and you get religious experiences. Like Saint Paul.

So who really needs πνεῦμα, call it what you will? And why? Some philosophers—those who seem to have struggled to keep up—will start bringing up ideas that are in many ways similar to the reification we saw from Thomas Harvey when he tried to find some anatomical substrate for Einstein’s genius. These are often along the lines of “So where’s the bit that does the soul thing?”, although often the phrasing is slightly more subtle, or a lot more devious. Let’s look at a few of these.

The Chinese Room

This first and perhaps silliest argument seems to be mainly directed against artificial intelligence (AI), but I warned you about deviousness. The basic “thought experiment”, first put out by philosopher John Searle in 1980, runs like this. A person sits in a room with a set of rules that directs how to manipulate Chinese symbols. A fluent Chinese speaker talks to the room, the person inside blindly manipulates the symbols, and apparently fluent responses emerge—but the person in the room doesn’t understand a word of Chinese! Something essential ‘has been lost.’

There’s a huge amount wrong with this approach. First, the argument can’t fundamentally be about ‘AI’. It’s deeper than that. Let’s say that we replace the “man in the room” and the associated rules with a multiplicity of people performing the same function. No one person knows all of the rules, so they consult among one another to establish the relevant rules, and produce an identical output to the original setup. Next, let’s amp it up a bit. Let’s bring in a few billion people. None of them understands Chinese—but the system still works. Oh wait! We can replace each person with a single neurone, and it still works. Hang on, we now have the neocortex of a human being, where none of the neurones understands Chinese, but it still works. Why would we expect individual components to ‘understand Chinese’?

This shows that Searle’s argument is not about a person sitting in a room. He is arguing against ‘functionalism’—by reifying ‘understanding’. His ‘missing secret sauce’ argument evaporates when we perceive his sleight-of-hand. Worse still, he doesn’t propose a diagnostic test that allows us to tease out whether the Chinese Room has what he calls ‘strong intelligence’ or not. He can’t. This is just wordplay about how unhappy he is. If you’re really bored, read his convoluted argumentation.10

The Great White Quale

Another weird argument you’ll come across concerns ‘qualia’ (singular: quale). The idea here is that the quale is defined by what it is not! We are told that a quale is “a subjective, conscious experience”, and also that (by definition) a quale is unique to the individual: “My perception of the colour blue”, “how the headache feels to me”, “the taste of this specific glass of wine”, and so on.

There are two reasonable ways we can view this concept. The first is that it is an internal, operating parameter of a specific brain in a specific context. This makes it inaccessible to anyone else—although perhaps we might still quantify it as machinery like functional MRI or magnetoencephalography become more and more sophisticated. But is it accessible to the individual? We have no direct phenomenological access to e.g. our 80 billion brain neurones, or indeed, our internal pathways—and it would be bedlam if we did! So our second, more mature model is that we have (a) the person who is perceiving the quale, and (b) the quale as information being received internally by that person. The very fact that someone can lament about the special nature of “how I see the colour blue” is already starting to convey information (data in context). They can now (logically) start relating the quale to past experience, other sensations, and so on.

Can you see the underlying assumptions with quales? There are two. The first is that the individual is somehow uniquely special. And yes, trivially, they are. They are made up of different atoms, they have a different history, different genes, different DNA methylation, and so on. But almost all of these differences are irrelevant to the big picture. They are overshadowed by …

The second assumption. This is the one we’ve already challenged—that we need to start from a position of difference. In contrast, the only reasonable option is to assume similarity, and work from there. And indeed, if my understanding of your feelings about your current perception of the colour blue is in terms of our communication inadequate, you can then proceed to do a multitude of things about this. You can ignore it as minor; or we can talk, and you can explain, as best you can—in a similar way to how you explain things to yourself, all the time. You can write a poem, or popular novel about it. I guess you can even philosophise about it, but this may be the worst option of all.

In other words, the ‘quale’ is one of (a) badly defined, (b) irrelevant, or (c) just another, slightly obscure and devious way of talking about your feelings—to yourself, or others. You can read up about the so-called “hard problem of consciousness” at this point, courtesy of David Chalmers, yet another philosopher. Together with other non-problems like ‘ineffability’, ‘philosophical zombies’ and whatnot. My they have been busy! Personally, I’d suggest life is too short. The ‘problem’ isn’t hard. It’s just confused.

Hameroff

It seems we also can’t escape the ‘quantum’ get-out-of-jail-free card. Some years ago, an anaesthetist called Stuart Hameroff persuaded ageing physicist Roger Penrose to go all in for (wait for it!) room temperature quantum effects being the main mediator of ‘consciousness’, this to ‘explain qualia’. They put everything into the kitchen sink here and give it a good stir—microtubules, qubits, bad philosophy, quantum gravity and even Gödel's incompleteness theorems. You can look this up too if you want, but the key indicator that this is madness is that last invocation, a sure-fire stigma of holy woo.

“But the evidence...”

You can see where I’m going. All of the above arguments were generated, not to address a problem with reality, but to address the internal problems experienced by slightly stunned philosophers. I’d suggest that practitioners of both modern religion and modern mysticism have similar issues. And these boil down to reification.

If we cast aside circular philosophical arguments that assume some sort of secret soul sauce and then try to prove it, we’re left with brains made of nerve cells and other components; our brain function is explained purely in terms of nerve physiology. The ‘spirit’ ancients conjured up is no more ‘a real thing’ than ‘a statistical distribution’. Ironically, we reify our own minds using mind projection!

This explanation is however psychologically unsatisfying to many people. We have to ask why this is so. I think there are two main reasons:

We have thousands of years of established belief, and all of the complex institutions we have built around this belief;

We want something more.

I can’t help with the first point. There may be need there—but convention doesn’t require extra explanation. It has its own inertia and is pretty much self-justifying.

Let’s explore that second point though, because it’s crucial. Brains are similar across individuals and even across species. People — and rats too — work off internal models of the world. We make models that resonate with what is going on inside the heads of others—other minds. We are social animals, and we desperately want these relationships to continue. When others die, we are also confronted by our own mortality in ways that are almost overwhelming. The need for something that persists outside of and apart from our own memories of lost people is a powerful incentive to seek evidence of this persistence.

We’ve also already established that there are certain advantages to having a tendency towards “false positives”. We are bias-prone. We will seek out and perceive evidence that confirms our tendencies and desires to see something more than is really there. When we Science all of this, the ‘mystery’ evaporates. And precisely for those reasons, not a single person of faith will buy any of the above. We still let the heart rule the head, despite William Harvey showing in 1628 that it’s just a muscular pump.

So I’m surely preaching to the secular choir. However, if just one other person has read through the above, and this has led them to ask whether their own brain is complicit in an unreasonable deception, well then, this whole post has been worthwhile. If this person is you, congratulations!

I’d now love to move on to an evaluation of modern artificial intelligence, with a special focus on large language models. But before I do, we need to examine at least one more thing in detail. Which is what we’ll do next.

My 2c, Dr Jo.

He had a Jewish wife, which may have dampened his enthusiasm somewhat. But he is recorded as saying in 1939 that:

“[the human organism is] manifesting itself as the truly perfected National Socialist State. The fact that imperfections have occurred, and will continue to occur, only goes to prove that in the National Socialist state, not a single person can dispense with the leadership. Hail to our Leader!”

The problems with Foerster were first drawn to my attention decades ago by my father, a gentle surgeon who read Foerster in the original German, and found it all quite disturbing.

The model seems more likely to derive from the work of Sir Henry Head and AS Campbell, based on clinical observations of herpes zoster eruptions. Brain 1900:23:353–523.

We should also be quite clear that the sanctioning of Foerster by the medical establishment at the time was completely contrary to the norms and rules established in Germany by the non-medical populace, going back to 1900.

No. Not those Methodists. John Wesley came 1500 years later.

My corpse also had seven lumbar vertebrae and lacked a left internal jugular vein.

Or even “auxiliary hypotheses”. Some will distinguish things like ‘spirits’ and ‘psychic energy’.

You have the potential to listen or see using suitable tactile modulation on your skin!

Incidentally, this is how William Harvey died—a stroke involving Broca’s area.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be too cruel about Searle’s logic (as opposed to the allegations of sexual harrassment) as causal reasoning hadn’t been properly worked out yet; but like some current proponents of LLMs as ‘AI’, he also doesn’t seem to understand modelling too well, as shown on page 419 of that original article.

Very interesting — as always. Not to disagree with anything you’ve said but I’d like to make mention of why the “clinical” explanation for our “souls” and (hence) lack of an afterlife, gods, etc are so “psychologically unsatisfying to many people.”

I think (I dare not say “I believe”) that this lack of satisfaction emanates from instincts rooted in our early human DNA. When the first pro-humans gained the first glimmers of insight about their natural environment and about themselves, they would have been confronted with a host of unanswerable questions. (This reminds me of Douglas Adams’ “Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy”in which a sperm whale spontaneously manifests at some considerable altitude above the surface of a planet… and it has about 2 minutes to come to terms with its own existence before it becomes raspberry jam!)

It became very useful, and conferred considerable survival advantage for groups of pro-hominids to invoke gods as the causes of the many events and processes that occurred in and around their lives: these events of course included deaths of parents, siblings and offspring, pleasant weather, foul weather, abundance of food and water or lacks thereof.

Point being that groups of similarly minded individuals with a common belief system for things that were inexplicable would gradually learn to work together—greatly increasing their chances of survival.

Over millennia some members of “tribes” somehow acquired the skills to become priests: either because through some accident they were thought to be closer to the gods, or quite possibly, because they were crafty and self-interested and found ways to exert influence over other members of the tribe.

100,000 years or so later, these survival traits are still ingrained in our “souls”…. And leave us with delusions about gods and the afterlife. They are there for us to overcome, using common knowledge and rational thought. But not everyone can do this (or wants to).

Terrific, as always. So reification, that’s the name of the game…